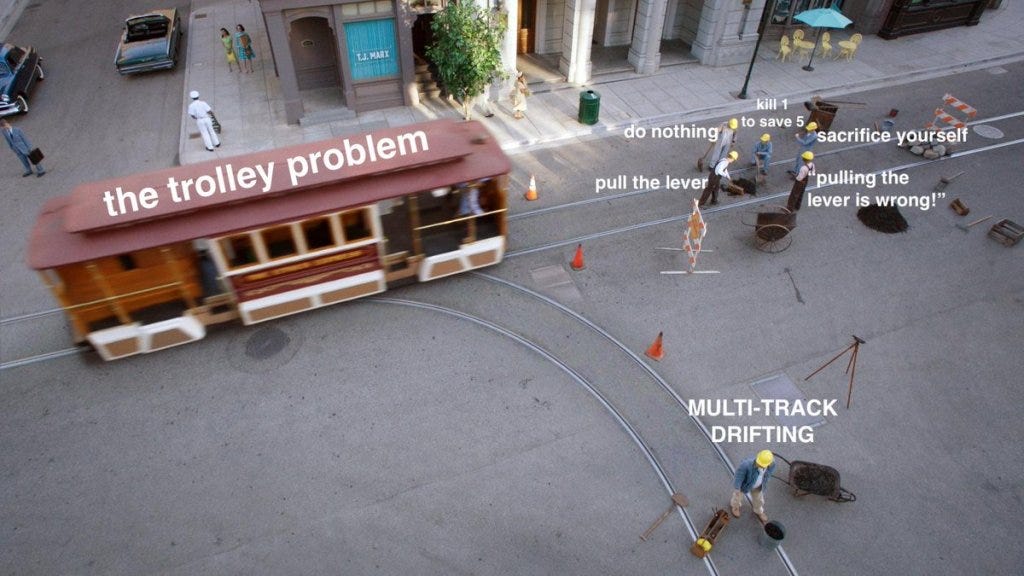

There is a popular thought experiment called the Trolley Problem. You will probably be familiar with it if you’ve done an ethics class, or watched The Good Place, or smoked grass who read Aristotle. The premise is this. A trolley is heading for a broken bridge. There are a number of people on the trolley who will surely die. If you throw the switch the trolley will be diverted, saving the people, but will kill a man who is working on track. Are we to go with a utilitarian approach: the greatest good for the greater number of people? Or do we look to our own ethical precepts - thou shalt not kill - as sacrosanct?

There are variations on the debate: different numbers of people, a different level of action, so instead of pulling a switch we have to push someone onto the track to stop it, or deflect a bomb from hitting a large crowd to hitting a small one. But the knotted brow of serious thought, the twisted sense that there is no good answer, just a tangled web of wrong and less wrong answers to unknot.

The origin of the specific phrase comes from the 70s when Judith Jarvis Thomson was framing the arguments of Philippa Foot and first called it the Trolley Problem. The thrust behind the Trolley Problem is supposed to prove consequentialism in our ethical thinking, which then has a real world political impact. Consequentialists believe that an action can be judged moral or immoral judging by its outcome. Deontologists by contrast would argue that an action is good or bad, regardless of the outcome - rules, moral duty etc.

My problem with the Trolley Problem isn’t really that I’m a deontologist, though I am a bit - as with most philosophical positions I tend to a pick n’ mix approach - it’s rather the nature of the question: the commonness and popularity of the question compared to how often it actually occurs in reality. How often do we have to kill one innocent person so five will not fly off a bridge? How many times do we have to deflect a bomb from a larger crowd into a smaller one? Following 9/11, these philosophical questions became the foundation for actual policy that guided the conduct of the various wars and the stripping away of humanitarian norms. The “ticking bomb” thought experiment was aired ad nauseum and even got its own TV show in Kiefer Sutherland’s 24. There is a dirty bomb/nuclear bomb/whatever planted in a major densely populated city. How many rules are you willing to break, Jack Bauer, in order to find out the location of that bomb? All of them, naturally. And so the moral justification for torture, waterboarding, the threat of execution or the murder of a suspect’s family, could all be countenanced. Zero Dark Thirty won the Trolley Problem an Oscar.

There was just one tiny problem. None of these thought experiments ever did crop up in reality. Torture - as the military have known for years - is actually a highly ineffective form of interrogation. Someone being tortured will tell you anything, and you will have nothing to help you. It makes the surrender of enemy combatants less likely, and the cooperation of locals likewise unlikely. Soft power evaporates. All that talk of Western values turns laughable.

Currently in the Middle East, Israel is using the consequentialist approach to commit genocide. Everything is permissible: the bombing of schools, hospitals, refugee camps, men, women and children and it can all be covered with the word terrorists. If we don’t do it, they will do it to us. No one in the IDF seriously believes that Hamas or for that matter Hezbollah represents an existential threat no matter what they say in their manifestos. But the human shields argument is a reframing of the Trolley Problem. We bombed a school and killed a bunch of innocent people, because Hamas has fighters in that school, bombs in the basement ready to strike Israel: so we are deflecting the bomb from the large crowd (us) onto the small crowd (you), thought the asymmetry of the casualties suggest it would be more accurate to say we are deflecting a bomb towards a large crowd of people who matter less. Herein lies the tribalism and racism.

These real world (mis)uses of the Trolley Problem can be contrasted with another problem which is discussed hardly ever: the Well Problem. I can’t find a Wikipedia page so I might be the first person to pose this problem. Here goes. You’re walking along, minding your own business when you pass a well. From the well comes the sound of someone shouting “Help! Help!" What do you do?

Now most people might think I’m joking. What’s the problem? You might think. It’s so obvious. You go and help the person down the well. But wait a second, what if you’re late for something, a date, or a film? Do you still go? What if you go and you help this person out and it turns out they’re a murderer or rapist? Aren’t you facilitating rape and murder? What are you doing to say to the victims and the families of the victims? How will you live with yourself? And if you rescue this one person, what’s to stop people becoming less careful around wells, maybe even wilfully throwing themselves down wells, confident that someone will come and fish them out eventually and spoiling the water in the process?

You might still think I’m joking. Is this a reductio ad absurdum, a favourite ploy of mine? You just help the person and ask questions later. It’s the sensible thing to do.

But let’s apply it to the real world. We witness many people asking for help every day. The homeless, the poor, the socially deprived, the mentally ill, refugees, economic migrants, victims of domestic violence, the list unfortunately goes on. Many of these people our governments are perfectly capable of assisting. In fact, if they moved some of the resources away from those bombs that they keep deflecting from one crowd to another in an endless attempt to resolve the Trolley Problem we could afford to more easily. And even though there’s a cost, isn’t there a moral duty *cough* deontology *cough* because after all we did dig the wells and weren’t as careful as we could have been in signposting them etc? And if we were to fall down the well, would we be obliged if someone helped us out (the golden rule)?

The Well Problem doesn’t seem to be a problem at all because all our instincts go in the direction of helping the person. You’d have to be a sociopath to feel no empathy, and even then you would still probably help. But we don’t talk about this problem because if we did we might start applying it to real life. We might shift it to the top of our political priorities. Instead we continue to talk about the Trolley Problem because this is a way of unethically talking about ethics. It’s a way of proving we’re concerned about ethics while trying to train everyone else to short circuit their own sense of right and wrong. By even thinking of bombing children as a moral dilemma means you’ve lost the argument. To even admit it’s an argument - and therefore open to the vagaries of an ultimately unknowable context - is to surrender.

Thomas Pynchon wrote once that if they get you to ask the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about you discovering the answer. I’ve often thought that is as good an observation as to explain and counter the rise of conspiracy theories in the last two decades or so. Those answers to “chem trails” are just irrelevant to the real world. But certain questions can only give you wrong answers and leave you choosing evil because you’re convinced that the only choice you have is between two shades of awful.

“Help! Help!”