The last time I met Sean Connery I was in my forties. I was at that age where you forget how old you are for years at a time. You have a vague notion but really who cares if you are 46 or 47 or 48? You certainly don’t. No one else looks at you with even a glimmer of interest. You move around the world. An adult, wondering how everyone else got so young, everything else got so small, everything got so crude. All the films and the books and the music, you’ve heard it all, seen it all, watched it all before. The risk is no longer killing yourself in some mad rush, but rather slipping into an ennui-inspired stupor of self- and everyone else- loathing. That dread would come back but I took up skiing and that seemed to help. I established a strict exercise routine and I went to night classes in the evening to pick up even more languages. It helped to parcel out the days into activity. My Arabic was now fluent, and I was becoming very interested in China. I spent a few weeks there every year. Flying back one year, I’d watched a film called The Presidio on the flight. It was not a great film, but there was a scene where Connery beat up a big fat hell’s angel using only his thumb.

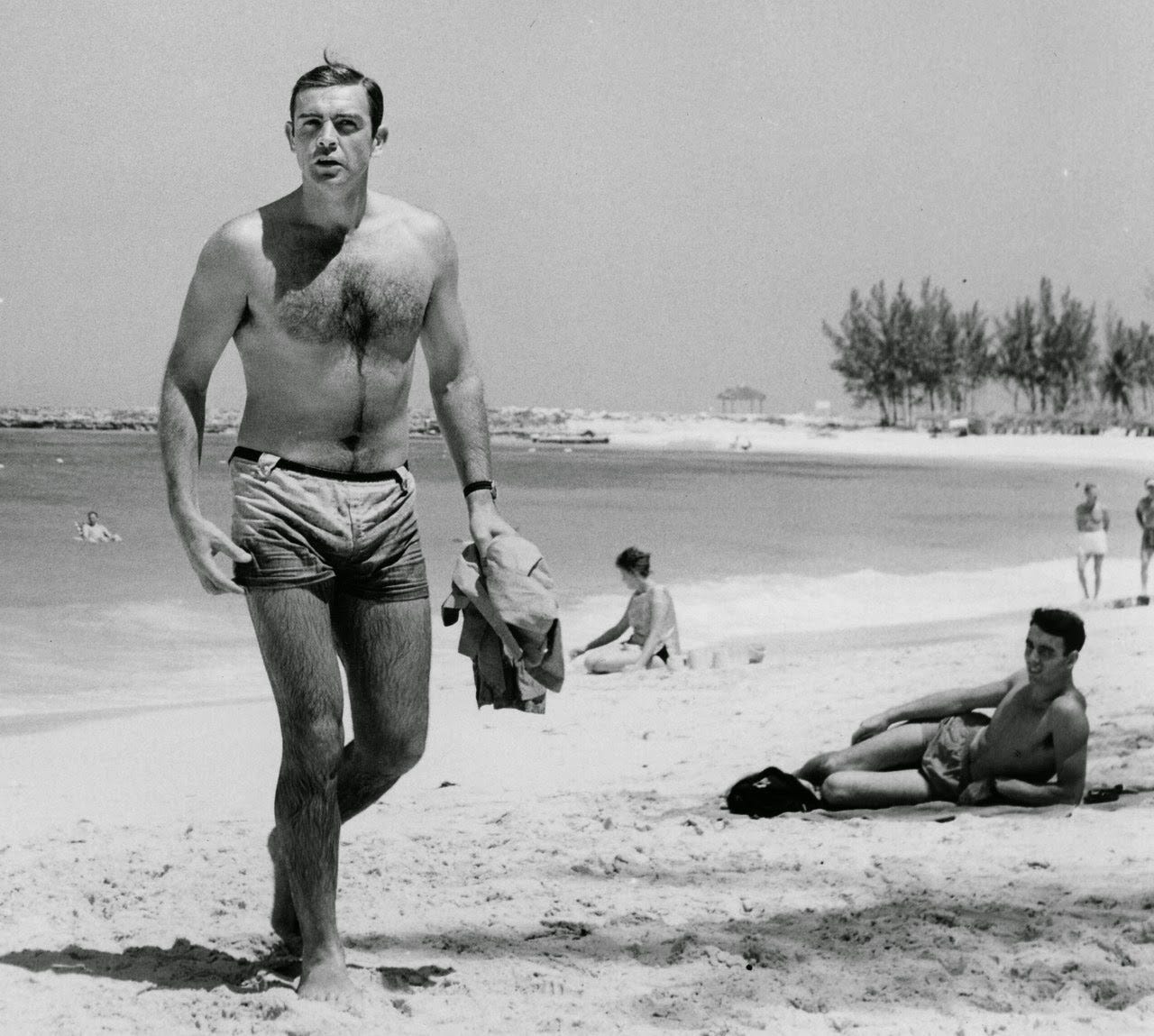

I knew where Connery lived, although he was often in poor health and so it was never certain whether he was there or not. Avalon Security had gone from strength to strength but had threatened to create more enemies than I wished to handle. The whole point had been to provide me with an alternative form of income while I was tying up loose ends from a previous life. In 2012, I let my enemies buy me out and incorporate our operation into theirs. I had made a lot of friends and had a lot of fun. Never drinking or taking drugs, I found being around parties endlessly amusing. I grew to enjoy the administrative aspect as well. The men and women who worked for me were tough and every now and then I met one with whom I shared a certain way of thinking, a certain absence of empathetic inclination and it was fascinating watching from the outside what someone like me looked like. I never met any of these people however who were as convincing as I was in the world. There were always the signs, the signs, the signs: the giveaways. I had been running on the beach and I ran passed him. He was walking with the aid of a stick. There was an attendant with him, but he sent her away. I turned around and began to jog back. I stopped at what I hoped was a respectful distance.

‘Hello there,’ I said.

‘Oh, for god’s sake!’ he grouched loudly to himself. Though it was obvious I was also supposed to hear. And then louder: ‘Yes! What?’

‘I’m sorry to interrupt your stroll, Mr. Connery, but I met you a long time ago. When I was a kid, and then again …’

‘Poppycock.’

‘No, I did,’ I said, catching my breath.

‘Where?’ he said.

‘I was … seven years old. The northwest of England. And then I met you a few years later, I must have been nineteen and I was on the ferry coming back from France.’

‘I have never in my life been on a ferry. Are you on drugs, boy?’

‘No, honestly, I’m not. I’m serious, Mr. Connery. I met you again. In an airport in New York.’

‘I don’t make a habit of meeting strangers in airports.’

‘We were in the lounge. You were with your wife.’

He shaded his eyes with one hand, though he was wearing sunglasses and a panama hat. ‘Do you have a cigarette?’

‘No.’

‘Then what earthly good are you to anybody?’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, but he was struggling to get something out of his track suit trousers. He dropped his walking stick and I picked it up and held it, while he shakily put a cigarette in his mouth.

‘Here,’ he said, handing me the lighter. ‘Light me up.’

I did, against the stiff breeze. He took a long deep draw and for the first time his countenance expressed something like calm magnanimity. He considered me once more, as if seeing me for the first time. ‘What did you say your name was?’

‘Sam Coleridge.’

‘Like the poet.’

‘Yes, exactly.’

‘Maybe I have met you somewhere before.’ He closed one eye and squinted at me. ‘Yes, yes. I’m beginning to see it now. But you’ve changed. When you were a boy you had hair like a girl.’

‘That’s right. I cut it off because you said that.’

‘I’ve had a good influence on you! Ha! I’m glad to hear it.’

I nodded as he started to walk, and I walked beside him. He took hold of my arm unthinkingly for balance and stability.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Actually, you’ve inspired me throughout my life. Watching your films and then, just having had the good fortune to meet you a few times. Each time you seem to have come in at a moment when I was in some kind of turning point, a crisis, and somehow you showed me the way.’

‘By telling you to get your hair cut?’

‘Oh, no. Much more than that. I mean you freed me. When I was a kid, I watched Dr. No and that bit when the double agent picks up the gun and you say “That’s a Smith and Weston” …’

‘And you’ve had your six,’ Connery said and guffawed. ‘That’s a great line. So cruel. That’s the sadism of the character right there. The way Fleming wrote him.’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘I didn’t realize that you were allowed to you know, not care. You shot an unarmed man. It was amazing.’

‘Well, that’s not quite…’

‘007, license to kill. That’s what I thought I needed. So, I did it. I tried killing on my own time, but there was no point. I lacked direction and that’s when I met you again and you told me to do something I liked. To follow my ambition so I joined the army. It didn’t quite work out the way I had hoped but I found it in the end my path.’

‘What do you mean? Killing on my own time?’

‘I knew I was a murderer,’ I explained, carefully. ‘It was something I could do, could enjoy doing. But you gave me encouragement and direction. I didn’t watch all your films, or anything like that. I’m not some sort of mad stalker. I wouldn’t want to give you that impression, but you were the human being who – I don’t know – gave meaning to my life, I suppose.’

‘My God, you’re actually serious, aren’t you?’

He stopped and I stopped too.

‘Absolutely serious, Mr. Connery. Taylor, my sister, was important too, to some extent. But she committed suicide and everyone else I know… she actually did commit suicide, by the way. [The day David Bowie died, no one knows whether it was connected.] I’ve made some of the others look like that, but in that case… it was true.’

‘You’re a fantasist.’

‘That’s what she would say. And sometimes I wondered. Could I truly be this lucky? Could I be living this life? But it’s absolutely marvellous what the world lets you get away with. Again I saw that you got away with everything.’

‘That was a bloody film.’

‘I know but films teaches us stuff, right? They teach us how to look at the world and how to move. When I walk through an airport, I imagine I’m you and I just glide. If I thought I was Sammy Coleridge, I wouldn’t be able to do it. But if I think I’m you, I can. And when I kill someone and I don’t feel anything, nothing at all, then I see you do the same thing. You never look sad, not really.’

‘You’re telling me you’ve really killed people. Sammy, I’m taking this seriously, so you have to tell me the truth.’

‘Yes, Mr. Connery.’

He looked me closely in the eyes, trying to read if there was any guile behind them, any hint of mockery. Was this some candid camera style joke? Was candid camera even a thing anymore?

‘I have something to tell you,’ said Connery after a long think. ‘But I’ll have to whisper it in your ear. May I?’

I nodded and he stepped forward and put his hands on my shoulders to balance himself as he leaned in. I could smell old people’s smell, an odd mixture of talcum powder, dried urine and cigarettes. His lips were almost touching my ear. ‘I just wanted to say, Sam…’ and he drove his knee straight up into my groin as hard as he could. I collapsed on the sand doubled over in agony. ‘That’s for scaring an old man.’

Nausea overtook me and I began to retch out my breakfast onto the sand as he started to pad away, leaning on his stick as in the distance I could hear his carer calling as she ran towards him: ‘Mr. Connery! Mr. Connery!’

He turned for a second and waved his stick at me: ‘And if I ever see you again, I’ll break you in two you little bastard.’

But I never saw him again.