I was studying English literature at Manchester University when I first murdered someone. There was no internet as such so the information I got was from the newspapers. Luckily Joseph Mipps being an American meant that the murder and the investigation were featured widely in the newspapers and spent two weeks on television with lessening space as the time went on and the clues dried up. I was able to get a lot of information about my first victim, but I made sure that again I didn’t keep any notebooks or scrapbooks, or clippings or anything like that. Even though the little 3D map of the crime scene included in one of the tabloids – the Daily Star I think – was very tempting. I didn’t talk about it except perhaps to respond to a fellow student saying something in the blandest way possible. Strangely, I found myself not exactly uninterested, but disinterested. I was mildly curious about how things would develop; if some alternate theories would gain ground; the reports of a witness’s account which was later to prove bogus. My interest in the case was simply to gain confirmation that everything had gone as smoothly as it seemed to have gone. Like with the witness. I knew as soon as I read the account that it was fake. Someone was exaggerating what they had seen or were building on something. I didn’t for a single moment feel any trepidation or fear.

My preparation had been exemplary and I had nothing to worry about. The police had nothing to go on. CCTV footage was being examined; physical evidence collected; hundreds of people had been interviewed, but so far, no real progress had been made. Theories spread by the newspapers were all wrong and pointed in many directions none of which came remotely close to touching me. In fact, they soon began to look into the actions of the victim. What was he doing? Wandering alone without his family? At that time? Why wasn’t he back at the hotel? Was there something sordid? Was it an assignation? Who was he meeting? The attack had been close and there were no signs of struggle. Could it be that he knew his attacker? Was there something sensitive in his work as an engineer? Was this some sort of espionage inspired assassination? Now, there’s a thought. Or was this an attack against Americans? Something vaguely terroristic. This was 1993 so that particular paranoia had yet to metastasize. But none of it came close to what had actually happened. I took some grim satisfaction in this, but I didn’t glory in it. I had prepared so long and put so much work and thought into it that I would have been astonished if it had not worked. A fatal blunder would have been unforgiveable. I had done my very best to minimize the role of luck. I had been patient. There had been a number of potential victims, but something was always wrong that night and I had been almost ready to give up. The time I needed to get on the coach back to London was drawing close and I was determined I should be on it, regardless of whether I had accomplished my task or not. It was very, very, very important. A rule. The other potential victims there had always been something off. Too many people on the street. An awkward position. Someone sitting in a parked car close by. A body movement that showed that they had suddenly tensed as if an alarm had gone off within them. Joseph Mipps was a Godsend. I watched the tearful Mrs Mipps at the press conference that was held in Paris begging for anyone with any information to please, please come forward. I saw a clip on the news of her being shadowed by snapping flashing paparazzi as she huddled in a scrum with her daughters, clutching at their collars as she rushed through an airport, having decided to go back home, dissatisfied with the efforts of the gendarmes. There was a holiday snap they used on the news of the victim, standing with the sun in his eyes, grinning and leaning back as if he’d just been shoved by a happy stick. His eyes buried in a squint. This is what we become. A photograph handed over to the police and then released to the media with or without our family’s consent.

I took cursory notice of the man in charge of the investigation, a short man with a hairless dome, a gaberdine overcoat and sprouting moustache but I didn’t look at him too hard. He would have no sudden revelations. There was nothing to be gained from shadowing his investigation. In fact, there was a danger in wanting to make the game more interesting. A temptation to taunt and prolong the story. The only way my efforts could be made public is if I were to do that and with the thrill of the thing gone that became an increasingly tempting idea. One to be resisted. The sudden climax of revelation would have given away immediately to the discomfort of confinement, as cold as a concrete wall.

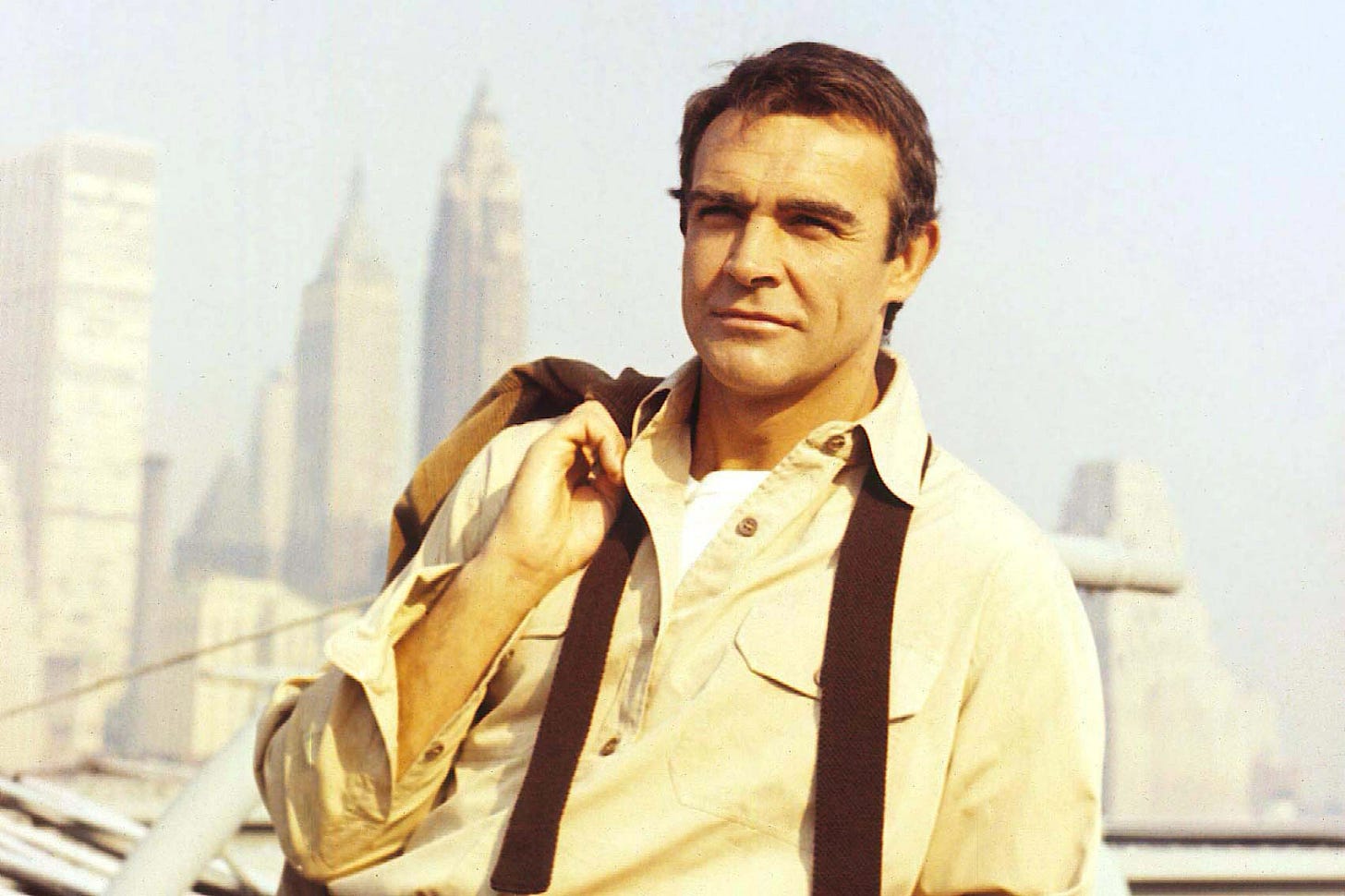

My second meeting with Sean Connery had given me much food for thought. Again, I decided that it would be better not to tell anyone. In fact, who was I going to tell? I had broken up with Carolyn and the affair with the comparative literature professor was proving ‘desultory’, a word which she used frequently herself. I was becoming disenchanted with my course of study and I realized that my life felt increasingly empty. The mission that had sustained me for a number of years – since I was 13 in fact – had been accomplished and although it had gone as well as could be expected, now I was left with this feeling of absolute emptiness. And to make matter worse, I could tell no one. This wasn’t a secret like the meeting of myself and Sean Connery. That secret was impressive, I could imagine people nodding and smiling, but I knew no one who wouldn’t react with horror and disgust at what I had done. I was under no illusions that the genius of it, the beauty of something thought out, meticulously planned and carried out so gracefully would be admired by few, if any. It was the kind of knowledge that would turn love into fear and loathing. Taylor or my parents, or my comparative literature professor, or Carolyn, or my fellow students would never understand. No one would. And this sort of secret is corrosive. It begins to scar and damage and eat away at the container.

This was the point I stopped following the slowly petering out investigation because the urge to confess – not to confess, but to explain, to expand upon – became almost unbearable. I sat on buses, looking at faces; in cafes and bars. I never drank. Or at least very, very, very rarely. I hadn’t given it up or anything so dramatic. I had never been a drinker. I imagine my parents had done enough drinking for the whole family and I didn’t feel any need to continue the tradition. It was almost as if we were being compelled to drink when we were young in the way other children were forced to eat green vegetables, so not drinking perversely became something that tasted of freedom and autonomy. I liked feeling the same all the time.

But as a student not drinking cuts you off. It made the nights out with fellow students unbearably long and dull, conversations becoming thankfully less audible as they spiralled and staggered into incomprehensibility, silliness and empty drooling sentiment to the pounding noise of a crowded smoke drenched nightclub. The gurning foolish faces, the noise, the strobing light, the relentless thumping techno. My life was empty. I had no human connection. No warmth of shared experience. I was cut off from my fellows and I spent more and more time physically training myself. Running, going to the gym, I joined the climbing club and that was the only kind of companionship I had that year. And still it was the companionship of the minibus and the belay rope. Against the rock I was alone once more, my feet pinched in my climbing shoes, my fingers scrabbling at a crack.

And this thing gnawed at me.

These questions.

Before the murder of Mipps, the whole mission from La Rochelle to Paris, had been simply to do a thing. An act. To see if it could be done. And without consequence. At least for me. It was an experiment. A social experiment. A philosophical one. An investigation into the workings of the universe and the true nature of power. The effectiveness of the state: the limit of the individual. Could I do it? If a tree fell in a forest…? If a man was murdered in a foreign city by someone without any connection, at random, could it be done safely? Would it make a noise? In my secret imaginings, there were rooms and basements in my mind, and they had accumulated furniture and libraries all to this end and now all that material was useless. It was like I had tested a bomb and it had worked.

Boom!

A huge explosion.

But now what?

I needed another bomb. I needed to blow something else up. But here I was repelled by the thought of a repetition. There was none of the purity of the first to the idea of a second. A second would be a retread, unless I began to add to the task artificial obstacles and handicaps. What if it was in broad daylight? What if next time I stayed in situ? But that felt so contrived. Should I try it lefthanded? Or tie my right hand behind my back? Should I try it blindfolded? On a unicycle? While juggling?

But it was true that now I had a huge murder-shaped hole in my life. My mission accomplished; all life had no meaning any longer. Why was I going running? Why was I doing yoga and watching what I eat? Why was I studying comparative literature and taking additional language courses in German and Spanish, still reading French novels in my spare time? What point was any of this if I wasn’t going to do anything with it?

And this is where Sean Connery had a point. Is this something that I could frame as an ambition? I had proven beyond any shadow of a doubt that I was very good at this. More than good I was excellent. Surely, I could use the skills that I had acquired; the natural talent I very obviously possessed – the coolness, the lack of moral squeamishness – and form this somehow into more than a hobby: a career.

So that’s how I ended up leaving university and joining the army. It didn’t happen suddenly. I was interviewed by the Army Recruiting Officer a number of times. He told me that the army had need of intelligent young men in leadership positions. He said that the army these days was a smaller more professional outfit, calling for a different kind of soldier, one who was multiskilled and flexible, able to adapt to any situation.

‘In a nutshell, Samuel,’ the officer said. ‘We don’t take riff-raff.’

I had to pass tests and a physical, all of which I was well-equipped to do.

All the while I continued with my university education as if nothing was happening. I wanted to keep all my options open. I had some doubts about the army. I valued my own personal freedom and the army meant submitting to someone else, submitting to a whole bunch of other people as a matter of fact, a power structure but in the end, I believed the upside was dramatically important. I would learn about weapons, survival, unarmed combat and hopefully I would have the opportunity to kill people with relative impunity. True, we had no wars going on at the moment, but it was only a matter of time. And even if I spent my years in the army during peacetime, the skills I would acquire and the contacts I would make would be invaluable. I could move up the service and perhaps even work in intelligence. I already spoke good French and my German and Spanish were better than intermediate. The recruiting officer was keen on me becoming an officer, but I didn’t like the idea of taking responsibility. I didn’t mind leading people or bossing people about, but I honestly didn’t think I had the skills to be imbedded in the structure in that way.

I saw myself as a squaddie: someone who could mechanically take orders, run miles in full pack, strip and clean his weapon and generally do as he was told. I saw myself disappearing into the machine of the army. I knew there would be many things I didn’t like about it. The close proximity to others, the bad language, the smelliness: that was all going to be trying. But it would last only four years initially.

I could devote four years to this.

And the university was boring me. I had given it the best part of two years. Hard to remember now, it was so strangely dull. Walking to and from the library and the lecture halls, the constant clamour of the traffic under low damp Manchester skies. The halls of residence and then the shared student house with endless arguments about cleaning rotas and mini-soap operas about electricity bills.

What was I to do? Who was I to become? I lay in my cramped bed at night and dreamed of people being able to fly by pulling on their hair. I’d like to visit other planets and travel in time. My ambitions sought to destroy the natural laws of the universe and live free in a dome full of fantasy.

The ghost of Joseph Mipps would follow me and help me in all my endeavours. Soon I believed I would have a small gang of ghosts, all doing my bidding and knowing only one thing. They wished they had never met me.