Joseph Mipps was a forty-two-year-old aeronautics engineer from Houston, Texas. He had large lensed glasses with thick brown plastic frames and small eyes. He was tall, just under six foot and had a paunch, a middle-aged spread. He was not fat or obese. He was married to a woman called Carol and had two young children Tammy (6) and Betty (8). He was in Paris on his holidays which comprised of a month-long tour of Europe that would take in England, France, Spain and conclude in Italy. Holiday of a lifetime. They’d saved up for three years. They were flying back to New York from Rome and from New York to Houston. He wore a polo neck tucked into his belted shorts and tennis shoes with white socks pulled halfway up his shin. His wife had told him to go for a walk while she put the girls to bed, and she would join him shortly in a local bar for a drink. All of this information I would only learn in the days and weeks following as I bought up a number of newspaper and reports of the crime and fitted the story of his pre-death life together. I want to be very clear on this point. I didn’t know who he was or any of these facts before I killed him. I had no impression of him at all. I didn’t find him obnoxious or disagreeable in anyway. I simply didn’t know him. I didn’t even see his face until I had already slashed his throat.

The strangest thing about killing someone was how easy it was to forget I had done it. Of course, once I recalled it, I could relive it in intense granular detail. But if I wasn’t thinking about it, then it was like it had never happened. It was in the murder box in the attic of my mind, next to the old Scalextric and the Christmas decorations. I suppose everything had gone to plan. Perhaps too much to plan. It was so smooth. The opportunity arose. The victim was on his own; the street was empty; the alley was close by. As he came up to it, I jogged up to him.

‘Pardonnez-moi,’ I said in a friendly tone. ‘Vous avez laissé-tomber quelque chose.’

And as he turned, I slashed his throat with the action I had practiced so long and hard that the motion was perfectly automatic, and the only imperfection was that it was perhaps too deep and almost took his head off. He was falling backwards as he clutched at where his throat now unexpectedly opened and his pumping blood. The heart pumps the blood so violently that you could fill a petrol tank with blood in less than a minute. It takes a matter of seconds to empty the body of its seven pints. My biggest concern was not to get any on me. I knew that he was dead. Not yet but very soon so I was turning away and scanning the street to make sure no one had seen me and was then walking away. I had the street map memorized so I wanted to be somewhere that wouldn’t look like I was walking away from this place even though I was obviously walking away from it. This basically meant tracking up to a parallel street and then circling back and up again. This only mattered for the first one hundred yards or so. Then I made my way to a metro stop – Cluny-La Sorbonne – which wasn’t the nearest one. This took me to the coach stop and I was on the coach – just in time – before it hissed out of Paris and headed into the darkness of the French countryside.

Had I done it? Had I achieved the ambition that I had been thinking about, mulling over, obsessed with, for eight years? Working towards with singlemindedness no one would ever have suspected, had ever suspected? The answer was of course: not yet.

The murder was the middle section. Act Four not Act Five. The sudden quick moment. I didn’t enjoy it. I took no pleasure in it at all. Over before it began. No sexual excitement or anything like that, though Dr. Habbermas would undoubtedly come up with something squirming deep down. The murder was an element in an equation; a necessary act in a sequence. Getting away with it totally was going to be the thing. It would prove whether this was a viable course of action. Whether that theory concocted in La Rochelle when I was thirteen years old would stand up to the test of actual adult experience and the real world. Could this actually be done? Carried out. In reality. Not just in your head.

On the ferry, I took my backpack up to the deck with me and unpicked the Canadian flag and then threw it into the wind from the aft rail and watched it fluttering briefly in the salty wind before disappearing. A man was standing at the rail further down. He came over and asked if I had a light. I did. Even though I didn’t smoke, I always kept a lighter. I had a vague idea that I could have used it as an entrapment for a murder, getting someone nice and close and open, but it hadn’t proved necessary. I suddenly felt the mad urge to kill the man here and now, just because the opportunity offered itself. Grab him and launch him over the side. But then I realised that this was silly, a silly and unworthy thought, entirely against the whole tenor of my accomplishment thus far. Stupid, self-destructive: everything I had tried so hard not to be. Giddy with hubris. As the man’s face lit up between his cupped hands and the orange light from the zippo which I proffered I almost took a step back.

‘Jesus Christ!’ I said.

‘Hardly,’ Sean Connery said. He held up the now lit cigarette. ‘But thanks.’

‘I…’

He was already turning to walk away. He turned back wearily.

‘What? And please don’t ask me for a bloody autograph.’

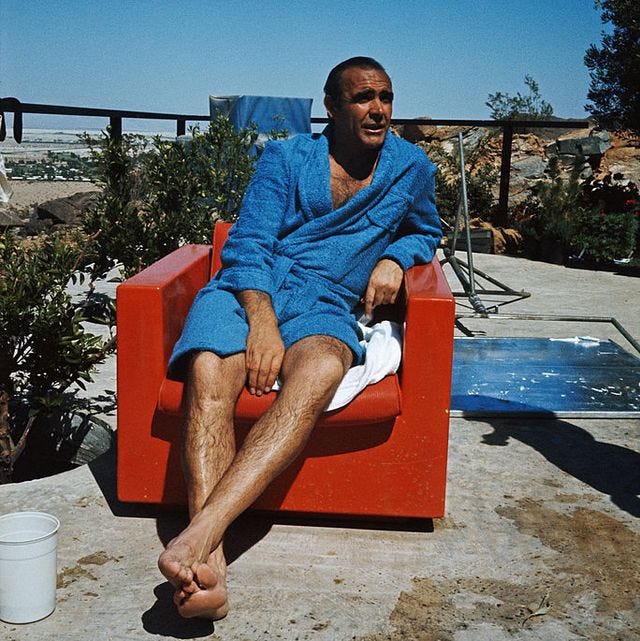

He had changed from when I saw him last. Older obviously. His hair whiter rather than grey. He was still a tall vigorous presence, but the years were upon him and he zipped up his jacket against the cold as he took a drag on his cigarette.

‘We met before,’ I said.

‘Did we now?’ he settled a gaze on me, trying to think where.

‘Yes, I was young, just a little boy. Hampton Rock on the beach in Cumbria.’

He smiled slowly and then settled his hand back on the rail and leaned close, so he didn’t have to shout over the sound of the engine churning below us. ‘You’ve cut your hair since then … let me see, Sammy, wasn’t it?’

‘That’s right.’

He squinted into the night darkness where France was receding into the distance. ‘And how has life been treating you in the interim, Sammy?’

‘It’s been good, Mr Connery. Okay I mean.’

‘But nothing spectacular, eh? Is that what I’m to understand?’

‘No,’ I agreed. It was as if he had looked into my soul. Deep into it. The accomplishment – or near accomplishment (I was still not in the clear) – of my one ambition had left me feeling empty, devoid of direction, with a wearyingly meaningless life stretching out before me. No glory to it. Was that all there is to a fire? ‘Nothing to write home about.’

He nodded and rubbed the top his head with his palm.

‘You will allow an older man to offer a piece of advice, Sammy?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Ambition is a risky thing. It sucks up a hell of a lot of energy and time. It makes you disregard some of the most important things in your life, your family and your friends. Even your higher values, perhaps. And worst of all it gives you a living definition of failure right there in front of you, all day, every day. That’s why most people shun ambition, have no time for it. They’re scared of it. But with me ambition was a challenge and it gave my life and gives my life shape and direction. Gives it meaning. Do you know I could have been a professional footballer? Manchester United offered me a contract.’

‘Yes?’

I did know this, but I tried to sound surprised.

‘I was a young man,’ he went on with a grunt. ‘I had the world all there before me. But I wanted to do something else with it. I fixed my sights, screwed my courage to the sticking place; and I aimed for that and ignored everything else. Do you have an ambition, Sammy?’

I nodded. ‘Yes, I think I do.’

‘Then dedicate yourself to it 100% and the next time we meet, I might be asking for your autograph.’

He pulled on his cigarette, a long draw that made the end glow like an angry planet and then flicked it towards the white wake of the ship, patted my arm, turned and was gone.