I was born at midnight on the 28th of June going into the 29th and my mother dithered, so the doctor put down the 29th and that’s what it became, and that story was a story she told as well. Again and again and again. Her dithering. My being born. The doctor threatening to slap her. I was born in the town of Ulverston which was then part of Lancashire but became part of Cumbria soon after I was born when the boundaries changed. I don’t know why they changed. My dad called me Samuel after the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Both my father and my mother liked intoxicants and didn’t take anything particularly seriously. Certainly, not my sister Taylor and I. I should add that our surname is also Coleridge and that’s why we got such ‘hilarious’ names. Not because mum and dad liked poetry, mind, but they did like jokes and as I said already, they dearly loved metabolising ethanol. It was their favourite thing.

We lived in a cottage that looked like it had been dropped onto soft ground from a height of twenty feet and sank, everything getting dislodged and going skewwhiff in the process. All the cookbooks and James Clavell and Leon Uris on the shelf slanted; the furniture itself leaned against walls that were not true. Nothing in the house was true. We had a slate roof embroidered with lichen which leaked when the wind accompanied the rain, escorting it in diagonally through the nooks and crannies. Our cottage was the last in the row before the railway crossing. When the trains going to the nuclear reprocessing plant went by late at night, with their fortified yellow carriages crammed with nuclear waste, all the bottles, jars, panes of glass rattled. The nuclear reprocessing plant was originally called Windscale, but they had an accident and changed the name to Sellafield, hoping that everyone would think it was a different place.

My mother was from Ireland, from a small village called Clougherhead near Drogheda. She described it as a small village. She said there was nothing there but a caravan site, a row of cottages and a church with the head of a saint and it was a very small head.

‘You could put it in your pocket.’

‘But did you?’ Taylor asked.

‘You are daft, Taylor girl,’ and gave her a slap because now mum couldn’t think what she had been going to say.

We learned not to interrupt.

Next door, Mr. Whillough had an ice cream van and would give us out of date blackcurrant lollies when he felt like it. And if Taylor gave him a hug and let him kiss her cheeks. One for each lolly. They weren’t nice lollies, but choc ices and ice cream all got sold. Feast was my favourite, but they went like hotcakes, Mr. Whillough said.

‘Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth,’ Mary said.

‘Tell that to the Trojans!’ said Larry.

Larry would get up while it was still dark and walk to the end of Feather Lane with his rucksack where the work van would pick him up and take him to the shipyard Vickers, where they were building nuclear submarines. They built an aircraft carrier there as well. HMS Invincible and we went to see it launched and I saw the Queen from a distance. The size of a Star Wars action figure, in a purple hat. Not close enough to say ‘I’ve met the Queen’ but I have seen her in a not on television way. So, there’s that. Twice as a matter of fact. She came to open Furness General Hospital and I saw her there as well but from even further away. Dad would take a book with him in his rucksack and a lunch box and a thermos. He would go into the bowels of the submarine and read Frederick Forsyth novels with a headtorch until it was time to come home.

Mother worked at Marks and Spencer and then at Asda, where she offered people a free taste of cake or some new tuna paste on a cracker or coffee whitener. She was cheery and very funny, and people liked her Irish accent, which she tended to turn up when it suited her. Though when she answered the phone she always put on an English accent. She called it her telephone voice. ‘Slatecross: 54200, Mary speaking,’ she would say.

We lived a little bit away from the village of Slatecross which was further up the hill and up towards the Lake District. We were outside the Lake District. Not quite beautiful enough. Not quaint. We went to nursery school there where I wet my pants at a Christmas party, something I’m still ashamed of today. We were playing hide and seek, and I didn’t want to come out of my hiding place and go to the toilet so I just did it right there. In my pants. When I was announced the winner, I had to come out with the front of my shorts a much darker blue than the rest of my shorts. It wouldn’t have been so bad, but my hiding place had actually been in the toilets, so I could’ve gone quite easily.

We went to primary school in a building that looked like an old redbrick church with a prefabricated pebble-dashed extension and a flat felt roof that leaked into a yellow plastic bucket, jutting out into the field at the back. The fell rose above the school and disused quarries crumbled at the top. Someone had burned a car in the quarry. It was a Citroen V7. We jumped up and down on the blackened skeleton until Pete Gillian cut his arm when he went through the roof and had to go to hospital to get injections.

I don’t remember much from those days. And I can never organize it into any appreciable chronological order.

I have flashes of memory. Like walking to a post office on a hill, that closed down soon after. I remember very briefly there was a second-hand bookshop that opened in Slatecross that seemed only to stock Alistair MacLean novels and that closed as well and no one else seems to remember it so it might have been open for a matter of weeks before the owners realised how bad an idea it had been. I remember the toys that Taylor had were all musical and the ones I had were to do with war or space or farmyard machinery. She had xylophones and little electronic keyboards and tambourines and a Stylophone with a picture of Rolf Harris on the box, and I had battalions of toy soldiers, a Millennium Falcon, cap guns and plastic knives where the blade went into the handle so you could stab people convincingly in the throat. This was part of a commando survival kit which I treasured particularly. It included a canteen, a compass, a code book and a special badge. Also, I had farm animals and toy tractors and things that I kept in large margarine tubs and put neatly away in a cupboard that had once been a larder.

I was a neat child. Taylor was also neat. Dad stepped on a soldier once in his bare feet and he forced me to eat the soldier until it looked like I was choking and then he made me bring it up by hitting me on the back until my tears came out of my eyes horizontally. He sometimes bought me Matchbox cars. Larry loved cars. I mean real ones. I remember a succession of second-hand cars, all bargains, all needed fixing: a blue Triumph Herald with a green door, a Renault 16 metallic brown, ‘the exact colour of dog-do’ as mum said, an orange SAAB, a red Maxi and a Ford Capri. Dad would fix them at the weekend, rummaging around underneath or within, and we would go for drives, long drives up the coast road and up into the Lakes. He drove us to Hadrian’s Wall, and we looked out of the windscreen as the rain hammered down, like it was trying to get in.

Sometimes we would drive across the country to Whitby and Scarborough, or to Uncle Mike’s in Yorkshire where dad would start arguing with his brother almost before he was out of the car and once dad and Uncle Mike had a punch up on their front lawn and dad knocked Uncle Mike out and Uncle Mike fell on a small family of garden gnomes playing cards on a toadstool table and broke it. Uncle Mike was older than dad and always treated him with contempt. Dad always wanted to impress Uncle Mike with his cars and his kids and even with his wife. ‘Look at how beautiful Mary is,’ he would say wistfully in Uncle Mike’s hearing. But Uncle Mike remained obstinately unimpressed and preferred to talk about Leeds United, something Larry cared not at all about.

Whitby was beautiful.

‘This is where Dracula arrived,’ Taylor told me.

Darth Vader was walking up and down the promenade with a plastic lightsabre. I got my photograph taken with him and Taylor on the other side. Her hair is over her face so you can’t even see her which was probably for the best. She was always grimacing. We wore matching cream-coloured Aran cardigans. Though it’s difficult to tell if this is a real memory, or one I created around the polaroid photograph, which I still have in my possession.

So strange that I should come again to Whitby, so much has happened. Of course, the facility is a little a bit out of town. We get a good view of it and the North Sea. But I mustn’t stray from the past into the present. At least not yet.

Next Christmas, we went to Yorkshire to exchange presents and dad got Uncle Mike a garden gnome and Uncle Mike thought dad was taking the piss and they had a fight on the lawn again, rolling around in the deep snow that had fallen and was still falling in thick slow flakes, sifting down from the low white sky. This time dad let Uncle Mike win. He said in the car on the way home it was the spirit of the season that stopped him from bashing Mike’s head in.

‘He’s jealous of you,’ Mary said.

‘Why on earth wouldn’t he be when you stand next to the sow he married?’ Larry said. And they laughed warmly. Their eyes watered. They stopped at a pub and we waited in the car. At one-point mum came out and gave us a bag of prawn cocktail crisps to share. Later, we drove home very slowly in the dark, mum asleep and gurgling and snoring and dad occasionally slapping his face.

I liked Uncle Mike’s house in Yorkshire. There was a tall TV antenna – a trunk-like pole – on the moor above the house. It had a light on top that flashed to stop aeroplanes from crashing into it. And there was a reservoir you could see from the bathroom window. Unfortunately, the house was at the bottom of a dairy farm and the whole place was drenched in the flat wet reek of cow muck. The first day you visited you couldn’t eat. The smell was in your mouth, the sandwiches, the ice cream, the jam, the cornflakes, the hundreds and thousands on the icing of the sponge cake, the water, the air. Everywhere. After a day or two, you didn’t notice. We played frisbee on the rec and bought sherbet, pear drops and kop-kops, and liquorice sticks which we pretended were cigars. The kids from the village were all friendly and everyone enjoyed playing together: the big kids looking after the little kids. They said ‘ace’ when we said, ‘top trumps’ and they said ‘by ‘eck’ when we said ‘flip’.

Taylor was two years older than me. She was a big girl for her age, and she had mum’s temper. Most of the time, Mum was sweet and funny but there were these niggles and peeves that she had. She was like a lovely meadow of spring flowers where someone had buried a minefield many wars ago and the mines were rusty and sometimes you could step on them and it didn’t matter and sometimes the lightest touch from a single paw of a butterfly and boom you were on your way up into the air before you knew what had happened: your limbs and blood falling all around in a soft brolly of rain. So, you could call mum, ‘mum’ or you could call her ‘Mary’, which she liked because it made her feel less old, but you couldn’t call her ‘mam’. Say ‘mam’ – just try – and before you got the second ‘m’ out, your ears would ring; your teeth would rattle, and you’d be wearing a red hand tattoo across your face for the next few days.

During the week, mum drove the car – whichever one it was – and she had to have Terry Wogan on the radio in the morning or Steve Wright in the afternoon. She worked part-time. She picked us up and dropped us off from our cubs and brownies and then when I was into my martial arts and territorial army phases. She didn’t mind you swearing but if you said fart, she would go ballistic. If you touched the radio, she would go ballistic. If you called her mam, she would go ballistic. If dad said anything about her drinking, she would go ballistic. If we got a note from school, any note, even something about a school trip or parents evening, she would hit the roof. She even hit the roof when Taylor won a prize for one hundred percent attendance. There was never any telling. And it didn’t help that dad thought mum going ballistic was the funniest thing in the world. When the noise, and the yelling and the crashing of things being flung against walls got too much, there were two choices really. You could either go up Feather Lane, cross the main road, up by the footpath up to the fell up to the quarries, up and up until you reached the skyline and looked all around you for miles.

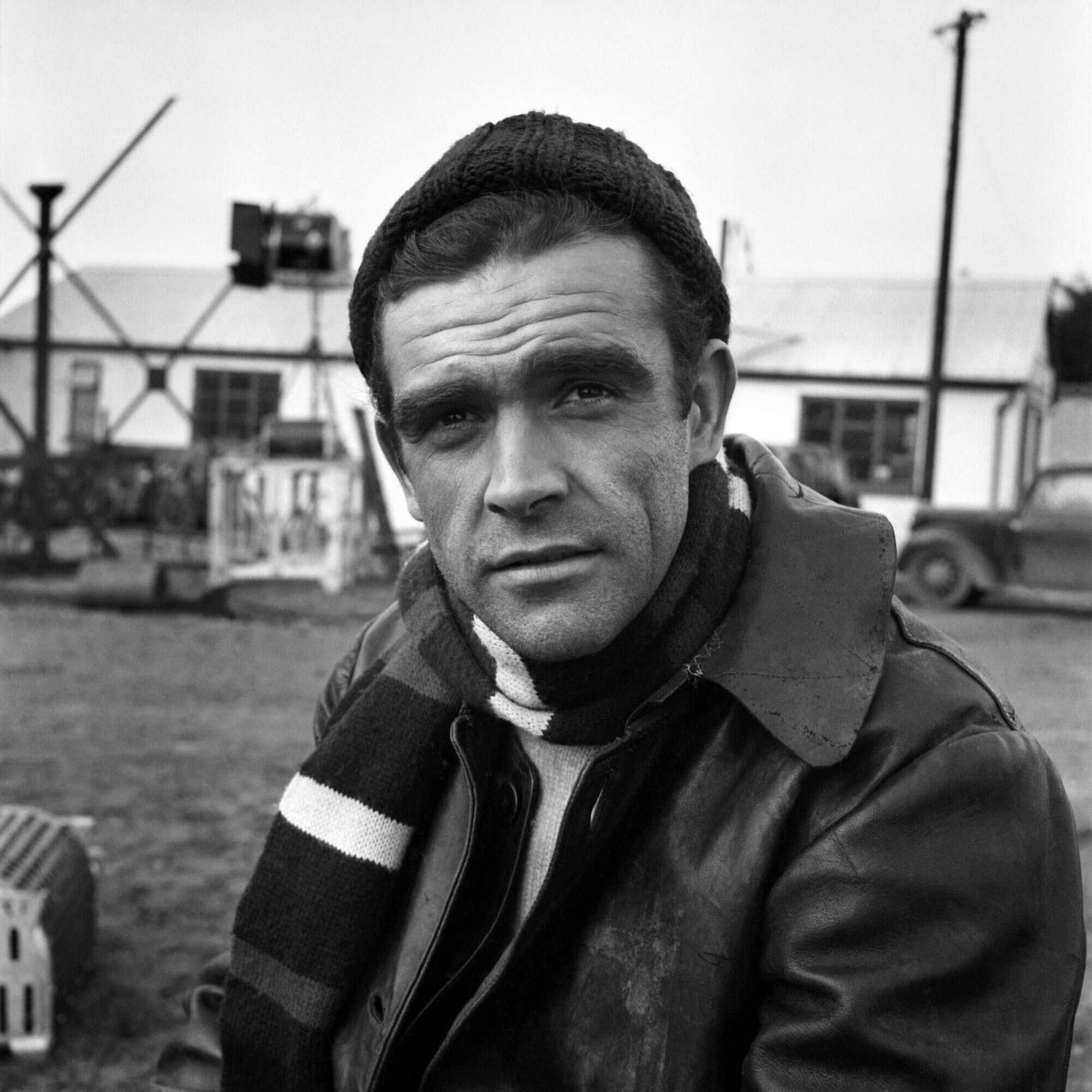

Or you could go down the lane, down across the railway line and down past the golf course to the beach, Hampton Rock and the cave where I met Sean Connery.

The decision was something I felt very deeply as a child and it almost makes me feel now that this decision had a fundamental impact on my character and on my life as an adult. A bifurcation. A splitting. That last word was just in case you didn’t know what ‘bifurcation’ meant. Don’t feel bad. No one knows what it means until they find out. That’s true of all words basically.

On the one hand, the fell was windy and lonely and frightening. You never ever met anyone up there and you could see everything spread out before you. The estuary, up to the lakes, Slatecross like a map of itself. And then up the road and down the peninsula towards Barrow and the shipyards with their cranes, skeletal in the distance. The loudest sound, a hammer hitting sheet metal sounded like a drip of water on a marble floor. You felt like God up there, looking down on everything, and it felt as cold.

At the beach on the other hand, I felt hidden from God and from everyone, in the cave like a monster’s eye socket. People came to the beach to walk their dogs and Jenny from the farm came to ride her horse Broadway. The Gillian brothers rode their scramble bikes up and down the spitting sand when the tide was out, but often no one was around and even if they were, they couldn’t see me in the cave, if I went far enough back and found a dry place to sit. The beach gave me the feeling of being in the middle of something but so deep and safe and calm. The sky soared magnificently above it, rendering everything epic. Sunsets looked like science fiction, murdering the Isle of Man in gore red hues. It was a beautiful place, but you knew you were hiding and just like when you played hide and seek, it made no sense unless someone at the end caught you.

Sean Connery would tell me – this is much later returning from Paris – he would tell me that games were played to be lost: ‘Every gambler I know, and I’ve known a few in my time, is waiting for the whoosh that sounds when you finally lose everything.’

I got Allan for my birthday when I was seven. I also got a toy Massy-Ferguson tractor to go with my farm and a box of Airfix American GIs. One of them was an officer. He had a raincoat and was pointing a Colt .45 service sidearm. My other favourite was from the Commandos set. A man crawled on the ground, a knife in his hand, ready to slash the throat of the first sentry he found. His hat looked ace. My friend Elliot Comb had a combine harvester that he brought around, and we set up the whole farm on the floor of the dining room under the table. We organised together and had a harvest. We had a bailer that I could attach to the back of the tractor and even produced little plastic bricks of bailed hay.

‘What are you going to call him?’ Elliot asked when Allan ran in and swept everything about with his wagging tail and stupidity.

‘Allan,’ I said.

Allan was a mongrel puppy dad brought home from the pub. I now think he probably improvised the bit about it being my birthday present. It gave him cover because he had been supposed to be here and helping with the party with my school friends and my friends from the village and instead he’d got out of the work van and instead of walking down Feather Lane, he’d walked on to Slatecross and gone straight into the Miner’s and got drunk and bought a puppy. Or won the puppy at darts. This being the countryside, people were always trying to give animals away, especially cats and rabbits. Cats were always having kittens and it was too expensive to go to the vet so most people would just drown them in a bucket if they couldn’t give them away. Poor things you might think. But the countryside is all about killing animals. You keep them around until they’re fat and then you kill them. At least dogs and cats had a fair chance of living until they died of old age. Not like the lambs, or the sheep, or the pigs or cows or rabbits or chickens. You know that practically all the animals in the world are animals we eat, and most of the rest of them are us. Mum didn’t believe dad about buying the dog for me, and though I did at the time, a couple of years later, I thought back to him holding the yelping Allan by the scruff of his neck and grinning and I realized that grin was the dawning of an idea. Mum was drunk as well. She had brought home a cake from Asda that had a cricket pitch on it in marzipan.

‘You like cricket,’ she asserted; daring me to say otherwise.

And I nodded. ‘It looks great.’

We ate pineapple and cheese on cocktail sticks and tuna paste sandwiches and jelly and ice cream and slices of cricket cake, and the kids got tired as it got dark and the sugar rush faded and they started to drift off home. Others were picked up by their parents who took a slice of cake wrapped in a serviette and refused a can of painfully strong cider. Mum didn’t argue with dad that night. It was my birthday and The Wild Geese was on television, so we all watched it. Larry and Mary wrapped in each other’s sodden arms on the settee. Taylor writing in her homework diary on the floor. And me cross-legged as close as I could get to the TV. I was eating a block of jelly. We used to get loads of jelly but instead of making it – you had to pour in boiling water and dissolve the brick of jelly and stir it and you put it in the fridge and then it would set after an hour or so – I’d eat it raw and mum didn’t mind because it was one less thing for her to do. She’d made some for the birthday party, but I’d kept a block aside for me to eat.

‘This is a good film,’ Larry said. ‘I like Richard Burton. He’s class. What a voice!’

‘And Richard Harris?’ Mary said.

‘Ack! You micks always stick together.’

‘Burton’s Welsh.’

‘So what?’

‘Welsh are just lazy Irishmen,’ Mary said, untwining herself from him and pouring herself a glass of cider from the can and then pouring it down into her without pause until the glass was empty. She could’ve drunk from the can but for her ideas of decorum. Rats do their business on cans, she’d told us more than once.

Larry barked with laughter. ‘Classic!’

Allan lay in front of me, watching the screen and I stroked his back and watched his ears swivel, which they did when he was happy. He’d been running around and yapping and barking, but now he was tired, and dad had given him a drink of beer as well.

I bent over him so I could watch him upside down. I could see the small square of the television reflected in his eyes as he watched. Richard Burton and Roger Moore were murdering black people in Africa, wearing red berets. Oh, how I longed to be a soldier.