I first met Arnie Cohen in the early noughts, soon after I had started working for Alan Parlon at the CIA. Following 9/11, the CIA contacted some Hollywood producers and sought their advice. The idea wasn’t totally without merit. Just almost totally. The most common reaction to people watching the Twin Towers go down and the Pentagon in flames was that this seems like a film. Movies had pretrained us in catastrophe and spectacular violence. There were theories that the terrorists themselves had sought inspiration from big explosive action movies. And so, the CIA realized they had been moving along in the usual trajectories. Fighting last year’s war essentially. The attack had been a veritable Black Swan. A paradigm shift. So, we needed to inject some imagination into the process. And where better than Hollywood?

Of course, the premise was flawed from the outset. The fact is there had been some pretty good intelligence predicting what was about to happen. My report had gained a reputation and I was perfectly happy to take the credit, but I had cribbed it from journalists and from other intelligence dossiers that were available in the run up to the attack as well as using Angela’s stuff. Alerts had been sounded. It was just people hadn’t been listening. George W. Bush had been handed a report about an imminent attack and had told the briefer: ‘Okay, you’ve covered your ass.’ Then did nothing.

Arnie Cohen was in his late twenties and had already made a series of midlevel films. The kind that had name stars, names that you recognised but wouldn’t necessarily make you go and see the movie. Also, directors who might have been quite something once upon a time but had been at least a decade away from their last hit. Either that or hot new talent who had cut their teeth on music videos or SNL but weren’t quite ready for the big screen. This isn’t me telling you this now. This is how Arnie himself characterised it. You’d start him talking and he’d go off like a set of windup teeth: perfect teeth in a healthily tanned tight wrinkleless face spieling away in a never-ending elevator pitch. But he’d sell you with a large dose of honesty, humour and self-awareness.

‘If you can show people that you get it, that you get how you are seen, even if this is to your own detriment then they assume everything else you tell them is likewise candid. The oysters here are all the proof I’ll ever need of your courage but be warned eating them can be like the final scene of the Deer Hunter. And you’re Christopher Walken. Spoiler in case you haven’t seen the film. And bullshit, I don’t care if I spoiled it. If you haven’t seen it by now and you’re over twenty-five you merit no consideration.’

I met Arnie first in some windowless conference room with Danishes, and sandwiches cut into triangles piled on paper dollies on paper plates on cardboard trays. Everyone was drinking coffee, a selection of juices from jugs – apple, orange and pineapple – and sparkling water. One of the overhead lights had a slight flicker giving everything a subliminal anxiety and the air-conditioning blew a cruel, unforgiving breeze. Arnie looked more like the stereotyped movie producer than the others: barrel shaped with a gaudy shirt opened to the chest bone and an expansive friendly motormouth manner. Another producer called Simon was dressed in cycling gear including shoes which had toe sections for some reason, which made him look like he had bare feet even though he was obviously wearing something down there. Aneeka was dark and Greek-looking, with a dry throaty cigarette stained laugh and an obvious love of profanity. They each came out with pitches they’d come up with, though I imagined that the work had been outsourced. A small room of writers had spent half a morning on them I was sure. There were photogenic targets and events. Someone mentioned the Superbowl, the New York Marathon, Times Square, Disneyland. The zeal with which Aneeka talked about napalming Disneyland from the air during a perfect hot holiday afternoon made me wonder if she had considered doing it herself. She certainly didn’t sound like she would be unhappy if it happened. ‘Imagine the guys in costumes all running and burning. Goofy and the rests of those effs. Jesus that would look good.’

As they talked and riffed of each other’s ideas, they got increasingly excited.

‘Hell, it’s so easy to get a job there, you could probably have a couple of insiders whip out machineguns and start spraying the survivors,’ Simon nodded vigorously.

‘I’d do the Oscars,’ said Arnie. ‘Block the exits, mounted machine guns on timers spraying the auditorium.’

Aneeka laughed. ‘During the In-Memoriam section.’

‘No, we wait until the best picture announcement, that way half the room is ready to die anyway.’

‘Roll a couple of grenades down the aisle,’ Simon said. ‘I bet that asshole Cruise would jump on one to save lives.’

‘Well, what Thetan wouldn’t?’ Aneeka said.

There were some more ordinary ideas.

A train with a dirty bomb being run into a major metropolitan area; a nuclear power plant being attacked or a missile silo. Most of it was totally useless. It was another example of fighting the battle we just lost again. Next time would be significantly different. They’d done the planes so it was natural to assume that security would amp up at airports. They’d have to go after something else. A soft target. A nuclear power plant or a missile silo was not that. Even Disneyland was probably not that. You might be able to get at something while the guard was down, but the guard was up. Most decidedly. In fact, it was beginning to have an impact on me. Suddenly, surveillance was going up everywhere; flight patterns were being recorded and analysed as was data from search engines and a whole other number of back doors. It was all algorithms and red flags. The side effect was that murdering people was going to become unreasonably difficult just at the moment that, paradoxically, – according to my white envelopes and green slips from Mr. Arrow – ever more people required murdering.

We had a break for coffee and because Arnie needed to smoke, I escorted him through the myriad corridors to the car park where he wasn’t supposed to smoke but no one would care. ‘So, who are you?’ he said. ‘What’s a limey doing sitting with these high-end CIA types and scribbling our nonsense on a legal pad?’

‘Some very interesting ideas,’ I demurred.

‘Bullshit,’ was his immediate response. ‘Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy the intrigue and your pastries are not without historical value. This croissant is what they ate in the 19th century. This actual croissant.’

‘They were a bit dry.’

‘Dry? I’ve tasted moister sand,’ he laughed. ‘What the … anyway back to my questions. You a Brit, or an Aussie or something.’

‘I’m English, though my mother was Irish.’

‘I like you more already. You want a smoke?’

‘No thanks.’

‘I bet it’s a story,’ he said. ‘You look like a guy with a story to tell. Look you’re smiling. I made you smile. I’m right, aren’t I? I’m funny because I’m true. Always, always true. So, go on: what’s your story?’

‘I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you.’

‘Ha, HA!’ he almost yelled, flicked his cigarette high in the air, slapped me on the back and we went back inside.

There was another hour of talk. A scenario where someone got control of the communication satellites and smashed them into each other to cause a global internet blackout was genuinely interesting causing Kessler syndrome or ablation cascade. I’d see the idea in a film a few years later and I wondered if it had come from our session. But they were beginning to run out of steam. As they left, Arnie gave me his card and told me to get in touch. He’d buy me lunch if I gave him a story: ‘even if it’s heavily redacted it’s going to be better than this shit, we’ve been doing here.’

I don’t know why I contacted him. I left it for another month, but then I was in San Diego to drown a local environmental activist and – lucky for me – ardent surfer. I had a flight booked from LAX so I wouldn’t crop up on too many passenger manifests where murders took place and, on a whim, I called Arnie. At first, he didn’t remember me, and it didn’t help that we had not actually used our real names. I knew his name, but I was that guy, the English guy, from the thing. The thing we weren’t allowed to talk about. I got a feeling he turned up at the famous Musso’s Grill just to find out who I was.

‘Oh you!’ he said, when he saw me at the bar.

We were led to our table by a large muscular Mexican.

Arnie gave me some of his spiel and then asked if it was okay to talk about the thing we had done and I told him we could keep it very general without mentioning names, dates or locations and he told me that they had all got their writers to work on their ideas. Except Aneeka: she seemed to have a personal fund of ideas: ‘You should keep an eye on her.’

‘She’s already on a list,’ I said.

‘Ha HA!’ he said. ‘Did they help? Our ideas?’

I shrugged. ‘Not really. But Aneeka’s were the best.’

He looked suddenly deflated. His chance to help the great mission, to serve, had not been realized. It was funny how nakedly apparent his boyish enthusiasm had been. Underneath his tan there was the grey pallor of death and his eyes became pools of deepest despair. Even his smile dropped like a winch somewhere had broken. He wiped his face with a hand and put his smile and his face back on with a vigorous rub.

‘Yeah, we got carried away thinking we were somehow useful. Still it felt nice for the fleeting moment we could credibly enjoy it. And so, what’s your story Sammy?’

‘My story isn’t particularly interesting.’

‘No. I bet you’ve killed someone though. I can see it,’ he broke a bread stick and pointed the jagged end at me accusingly. ‘Did you kill someone?’

‘Not today.’

He burst out laughing. ‘Not today! Ha HA.’ He had this curious laugh that started quiet and built up. ‘You’re funny for a G-man or whatever the Brit equivalent is. What is the Brit equivalent?’

‘MI6 or MI5.’

‘What’s the difference?’

‘Nobody knows.’

‘So, which are you?’

‘Neither. I’m out. A private consultant.’

‘That’s why you’re here,’ he crunched on his bread stick and then his salad arrived. His nose wrinkled at the sight of it in absolute disgust. ‘Fucking vegetables,’ he almost spat in it he looked so sad.

My steak looked good. I caught his expression and cut it in two, passing half of it to him on a bread plate.

‘To hell with the diet, am I right?’ he grinned.

‘Everything is a diet,’ I told him.

‘Wow,’ he said closing his eyes as he munched on the blood sopping beef. ‘That’s … you know … deep.’

‘That’s what I was thinking. I don’t just want to give you my story. I mean the story I’ve got. I thought I might write it down for you.’

‘What? You brought me to lunch for screenwriting lessons?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Not exactly. I just don’t want to give you my story though like that. And anyway, this isn’t my story. I couldn’t do that, or they’d have me shot.’

‘They still do that?’

‘Nowadays? Absolutely.’

‘Absolutely? Listen to you! Your voice has changed.’

‘It has?’

‘Sounds more American-y.’

‘I don’t think it ...’

‘Okay, so whose story is it?’

‘Let’s just say a colleague. I’d have to dress it up, but there’s a nice twist and I think… I don’t know but I think it would make a good movie. Especially these days.’

‘Okay,’ he said. ‘What you do is you write it out in prose as best you can. Like a short story if you will. This is what we call a treatment. It can be any length. A couple of pages are good, but if you want to go into more detail that’s fine too. I’d go for the short one. No one – including me – is going to read more than two pages unless they’re really into it anyway, like for real money. When you have it you can send it to my office, and I’ll have…’

‘No, you see I couldn’t do that.’

‘What, because of the material? The secret element?’

‘There’s no point exposing myself, or the people involved, if it isn’t going to go anywhere.’

‘Or exposing this colleague of yours.’

‘This isn’t autobiographical,’ I said. ‘It’s something I heard about somebody and it’s probably apocryphal.’

‘Based on a true story, huh?’

‘Sort of. Listen I did kind of write something down. I’m not very good at speaking.’ I handed him the envelope. A white envelope – but A4 and without a green slip inside – and laid it on the table.

‘Whoa! You Zelig motherf…’ he said, lifting it and weighing it with one hand. ‘That’s a little more than I was expecting but this steak is good and you’re intriguing so I’ll take it home and give you my two cents for what…’

‘No,’ I sa id.

‘What?’

‘No, you have to read it here.’

‘I can’t … Do you know what would happen to me if people saw me sitting here reading a treatment with the Goddamn writer sat opposite me? I’d be laughed out of this town. At least. Louder than I already am. And it’s too long.’

‘Read the first two pages. You said that’s all you needed to read anyway.’

‘Condemned out of my own mouth.’

‘Was the salad not to your…?’ a waiter stood beside out table bent at a certain angle.

‘Yeah, just take it away,’ Arnie waved him off. ‘And bring another of whatever this is and two more of these. You not drinking, Sammy?’

I shook my head as he finished his drink and then reached across the table and took mine.

‘Last of the lunchtime drinkers,’ he said. ‘The noble end of a dying breed.’

Then he sighed and took the pages out of the envelope. He read quickly at first, glancing around in the hope no one was watching. It could be mistaken for a contract or something else to do with money. Then he went back to the beginning and started reading again. He put the paper on the table and leaned over it with his hands supporting his head, his fingers massaging his temple.

‘Okay,’ he said when the steak came and he chopped it up into pieces quickly and methodically and then propped a page up against the mineral water and read as he popped chucks of meat into his mouth, one after the other, grunting in carnal satisfaction. He didn’t read the whole thing. He went back once more and read the first page. Then he put the whole thing back in the envelope and handed it back to me. He rolled the ice around in the bottom of his glass.

‘And that’s – and please I want you to be totally straight with me here Sammy,’ he put a hand on the envelope: ‘that’s not you?’

I shook my head. ‘It’s a bit of a legend. I don’t think this really happened. It’s just when I saw you guys last month and you were all talking and pitching those ideas, I thought I should put it together. I thought this was as good a story as any. I’d never thought of it before.’

‘And you haven’t shown anyone else this?’ he said. ‘Another producer? Your colleagues? An agent? You don’t have an agent, do you Sammy?’

The thought seemed to horrify him. He clutched his chest theatrically.

‘No,’ I said, shaking my head again.

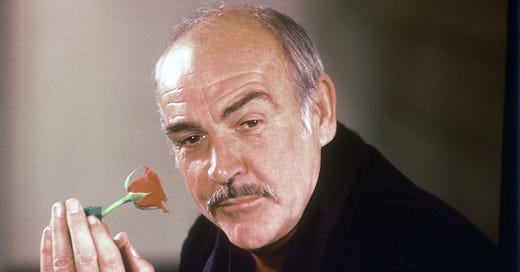

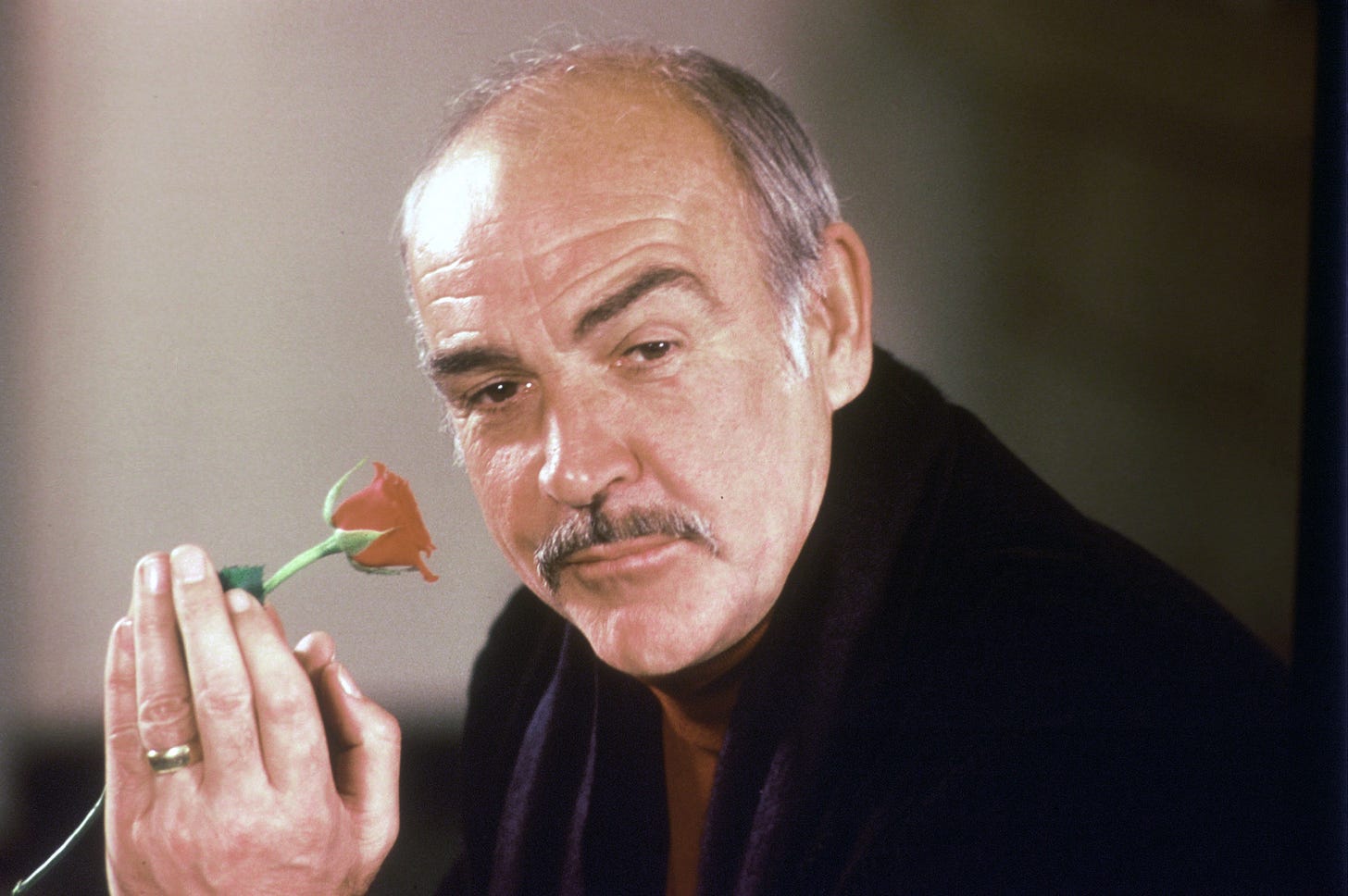

He was lost for a moment in thought and didn’t even seem to notice himself ordering ice cream when the waiter came to clear everything away. ‘The thing would be to get Connery to do it,’ he said wistfully.

‘You think he might be interested?’

‘I doubt it,’ again Arnie’s face fell. It was like he’d been running up the side of the hill and he had suddenly fallen into a very, very, very deep hole. ‘It would sort of ruin his public image and then after that League of Extraordinary Bullshit film, he basically retired. Still, that would make it fun. We might need him to be in it a bit more. Or whoever we end up on.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘We pick someone else, roughly equivalent. Burt Reynolds is still working. Jimmy Caan is cheap. Or Michael Caine. Roger Moore would be an obvious replacement. Have you thought this might be a book?’

‘What? No. Who reads books?’

‘Salient point.’

‘You liked it then?’

‘Liked it? I loved it. I’ll take out an option on it right now. Today.’

‘Really?’

‘No fuck no. You’ll need to rewrite it first. Don’t worry. I’ll give you notes.’

‘I’m not sure about that,’ I said.

He spluttered on his ice cream. ‘Oh, so the artist has arrived, has he? Listen buddy, film is a collaborative business and so you have to be a collaborator. And if you think that has dark associations because of the Nazis during the occupation, then you’ve started to get the idea. At the moment, it’s too dark. Dark is good. Ever since Batman began. We love dark, but you have to keep it within certain limits.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

It was weird that we sat opposite people and we ate and on the table all the time there were these weapons. How trusting we had all become. How naïve. How many times had I thought of plunging a knife into someone’s throat or a fork into someone’s face? Or spooned out someone’s eye? All in the middle of a meal, while they’re innocently troughing through their lasagne.

Arnie carved a little excavation in his ice cream and ate thoughtfully. ‘There are a few obvious things to change. And that’s good because if this is based on anyone you actually have knowledge of, it would be a good idea to put some blue water between you and them. So, for example, just move the whole thing to the states. No one wants to see Britain unless it’s Harry Potter or James Bond and even then, it’s usually only Scotland, London and everywhere else in the world but England.’

‘Okay.’

‘The other thing is the very first murder…’ he was at a point in his ice cream when there wasn’t much left, and he was having to concentrate on having to capture melting nubs.

‘Go on.’

‘You can’t have him kill an eight-year-old girl right at the beginning. As his first victim. It’ll alienate everyone. You want a serial killer like Hannibal Lecter. Someone we can kind of get into. Change it to a forty-year-old man. A fat white American and we’ll be rocking and rolling. Everyone will be with you.’

‘Really?’

‘We don’t mind murder, but we can’t have him punching down. You know this, surely? Hey, did he really kill an eight-year-old girl?’

‘Who?’

‘The guy who … you know …’ he waved his hand. ‘Who this is based on?’

‘It’s not based on anyone.’

‘Yeah right. And it’s definitely not you.’

‘Yes.’

‘I wouldn’t be having this conversation if I thought it was you,’ he assured me. ‘I’d be running into traffic with my hair on fire.’

In the end, Arnie did buy the option and we signed contracts that afternoon as he complained about his ruined diet. He had filled his pockets with candy bars he bought from the machine in the lobby of his building. The money was nothing, but it showed he had faith in me. I also wanted him to leave some kind of paper trail so that if he went off with my idea, I could show that he had stolen it from me. On the plane back to New York, I intended to reread the treatment, but I fell asleep and for several months I thought nothing of it. I was spending a lot of time in and around Baghdad and then I was six months in Guantanamo Bay ‘observing’.

When I got back home, Arnie had left me a bunch of messages. Many were notes for the copy of the treatment that I had – after a lot of badgering, badgering, badgering on his part – finally sent over. I was not very pleased with it, but he liked it. Every step I took away from what I saw as the truth made me feel like there was no real point in doing it at all. The original idea had been something like hiding in plain sight. The idea was to me a colossal joke. Just put it out there. A confession of sorts but with no sense of guilt, no remorse or even triumph, particularly. It just struck me as something that would be good to have in the world. For a while, I had been wondering when I was going to be caught. I didn’t relish the idea and my Plan B was suicide. I had acquired various pills and concealed razorblades, but then I’d get unexpectedly excited somewhere and use them on someone else and I’d have to go about getting some more.

Around this time, I was discovering the dark net and that was a good place to get what I needed, but the risks involved still felt unnecessarily high. Again, I stress: I didn’t want to get caught and the whole fascination for me had been in getting away with it. From the very beginning the elation I felt was in that sense of walking – not running – away from something terrible and feeling the bonds that tied you to the horror and the blood getting thinner and thinner, gossamer thin in fact, and then snapping. But wouldn’t it be marvellous to be caught and to kill myself but to leave behind a permanent record of what I had achieved?

And not only that, but for that to have been consumed and even loved by people as a major piece of art. Or at least a movie.

Also, the very act of writing – this very act of writing – had its own morbid pleasures. My ghosts were fading. It had started off a village where I knew everyone’s face but now, they were a small town and some of them blended one into the other. Murder had become routine. Writing about it brought back that first hot flash of joyful revelation. I felt young once more living in the memories of years ago. Writing felt like the extension of murder by other means. There were so many cruelties possible even within an accumulation of words and phrases. So many deceits and misdirections. Very slight touches could turn the ball in one direction or another. For my name to be known. Not famous necessarily but known. I would be interviewed perhaps for a podcast. And knowing Arnie – and we met another couple of times in this period – I knew he would want me involved in the production, if only to save money on a technical advisor. He liked having me around. He liked talking to me. He said there was a ‘frisson’, a word I’d heard somewhere before – I’m not sure where. Jennifer probably.

The treatment had got longer, and he said that it might be an idea for me to write a book. For it to be turned into a book. It didn’t really matter to him, because he was going to get some hired screenwriter to turn my treatment into a script. We talked over the phone about credits which I’m ashamed to say I was quite insistent on. I wanted a ‘story by’ and a screenplay credit. He said that last part might be difficult, but I bought a copy of Final Draft and watched some YouTube tutorials. It wasn’t hard in the end to put something together. Enough for me to get at least partial credit. All I had to do was convert the format. He said if I wrote it as a novel then I could get a ‘based on the novel by’ credit and plus the novel would be credited to me alone.

I liked the sound of that but then I began to wonder if some of my old bosses – Ollie to be exact – would appreciate it. And what about his father Mr. Arrow. Might he not object? I had an honest feeling, he wouldn’t.

And if he did, then there was another solution to consider.