When I left the army, I had killed three more people and my mother had died. One was a young woman working in a petrol station while I was in Northern Ireland and the other two were a couple in a secluded car park near a local spot of outstanding natural beauty in the Peak District. None of them was a properly planned operation. They were killings of opportunity. But this didn’t mean that they were in any way a rash venture or a so-called crime of passion. I don’t want you to get the idea that I had become some kind of crazed killer, running around the streets trying to satisfy some gnawing blood lust, with my pants around my ankles and knives taped to my body protruding and ready for slashing embraces. That wasn’t it at all. I was in the army for more than four years and in that time, I only killed those three civilians. Of course, the irony that I was being trained to kill our national enemies and I only ended up killing those very people I had sworn to protect was apparent to me. But I was worried that I was going to become rusty. And I wanted to show if only myself that when an opportunity arose, I was still able to do it. I was keeping my hand in.

In the aftermath, I felt some relief. My mind could be engaged in severing every link that might prove suspicious. But it was almost like an instinct. I knew I could kill that target and I knew there was nothing around me that would incriminate me. I knew that I could move freely, and I knew very few clues existed between myself and the place. In the case of the Peak District, no one who knew me knew I was there. I had – I admit – gone there on purpose to see if there was anyone around to kill. But that was the extent of my planning. That and dark clothing and the awareness that should the opportunity arise I was ready to seize it. The killings were two years apart and so there was no way the two crimes could ever be connected. In the case of the Derry girl, there was a heightened alert and a worry about the return of newly dormant terrorist factions, holding an uneasy truce. With the couple in the Peak District, a man – Geoff Peiter – was arrested and went to trial and was found guilty. He had found the bodies and was something of a simpleton, trying to revive them and then moving them about and then finally panicking. He was now covered in blood and had left fingerprints everywhere but still he went back to the pub where he had been drinking – he was already drunk – he called the police from the payphone outside the pub; had another drink and went home. The evidence against him was purely circumstantial but he also had a reputation as something of a loner and he fitted into a perfectly acceptable stereotype of a murderer. His glasses for instance were too large and he had hair that stuck out in tufts on the side of his misshapen head. Note to self: don’t be weird. Or at least too weird. The British will accept almost anything except being a bit weird, regardless of the famed English fondness for characters and eccentrics. Like a lot of other things, it simply isn’t true in reality.

I could follow the investigation of the crime in the newspapers much more easily than I could with the Paris murder, and there were bulletins on the news and even an episode of Crime Watchers devoted to the Peak District murders. Before Geoff was finally arrested – it took the police six weeks before they decided to go for it – a rumour went around that a serial killer was at work and everyone got very excited, serial killers being a big thing in the nineties, a bit like zombies were later. ‘Savage’ was the word that they had used in the newspapers. A savage attack. ‘Frenzied’ would come up as well. Having read some of the literature, I knew that this was what they needed to look like. It would have any investigation looking for a very particular type of suspect and one who, by design, looked nothing like me. My profile would have been colder and more efficient. Like the guy in Paris, whatshisface, Matt Kipps, I want to say. The single lethal blow. Clinical. Walk away, confident that the man will die within a minute, a minute and a half, tops. A professional job. But as a friend of mine, Ollie, once said nothing is professional unless you get paid to do it. Anything unpaid and you’re an amateur or a fool, no matter how good you are. And that still irked. I had assumed that the army would eventually provide me with some opportunities but here I still was playing for the amateurs.

We did get some assignments that took us close to conflicts: areas that were dangerous. But our rules of engagement so far never called for lethal force and it was just my luck that I entered the British army with the Falklands a distant memory and the first Gulf War wrapped up with hardly any fighting at all. Certainly not by British Paratroopers. The Irish had settled down a good deal and in 1998 would sign the Good Friday agreement. I’d be out of the army by then but even before that our role had been wound down to something non-confrontational and boring and anyway, I only got a three-months ‘crack at the Mick’. It was no longer a shooting war. Aside from the firing range and some elaborate war games (which were fun), we were no longer a shooting army. We would watch the news our antennas twitching whenever something looked like it might kick off and we could reasonably be expected to intervene. So, you can see that my killings – given the time period and the huge amount of boredom stretching three hundred and sixty degrees around me – prove me an absolute model of restraint. The intelligence work I hoped would be far less reputable and restrained but I had a fortnight of special leave before my training began and I needed to resign from the Parachute Regiment.

I went home to visit my parents. They were happy to see me but my dad was a little wary. He thought that I might be aggressive or something. He didn’t understand either of his children. First, they had been there, an amusing nuisance, a noise in the background, later little people to watch television with, to fetch things from the fridge, to kick up the backside so they did funny little jumps and flinched when he entered the room, or who came in with news of the world outside. And now Taylor had disappeared into the murky depths of London and except for the occasional phone call (‘desultory’, as my comparative literature professor would have called them), she was a stranger. They hadn’t actually seen her for a year. And what to do with me. This large boy – I had grown to be a six-footer – who had the sticky-out ears, but now seemed like a totally different thing. An adult. Fathers must have a moment when they realize that their sons could totally beat them up. I mean annihilate them. It must come as a nasty revelation. A step closer to death and dissolution. The memories of the casual cruelties and swiping slaps must tickle the conscience like cowardice. So, it was for my father.

But there was a step that happened before then I’ve left out. My mother still had her job as the sales representative who was supposed to push promotions at local supermarkets, interrupting shoppers to shove something free in their faces. She had gained promotion over the years and now had a team of other women working under her, but then after a few years of enjoying the higher wages, she began to slip back to where she had started. This was mostly voluntary. She didn’t like travelling and her new responsibilities required it. She had a real problem dealing with other employees. She could be nasty, and her chumminess only made up for it to a small extent. Her nastiness and chumminess I now recognised as her hungover alter ego and her freshly renewed drunk counterpart. It’s hard to work out which one was the more authentic as she spent roughly half her time as each one. I had been home several times over the years though I found myself restless in the house on Feather Lane. There was no peace. They made an effort to welcome me and we would have a Chinese takeaway, but they didn’t know what to do with me or say to me. That I didn’t drink was a problem. Drunks, except for Ollie, don’t like sober people around watching them. They became self-conscious and irritated. I found myself going for longer and longer walks along the beach or up the fells. Always those two destinations. Though now I could drive, I would borrow the car and take myself deep into the Lakes or up to Hadrian’s Wall. At which point, I was vaguely aware that there was no real point returning to Feather Lane and my parents’ cottage. My mother had put on weight and my father had lost it. He was having health problems, gall stones and he kept having small accidents at work. When he had the first one – breaking his arm – he was paid a significant sum in compensation and had a month and a half paid sick leave while his arm healed. I wouldn’t want to suggest that the subsequent accidents were not actually accidents but I’m sure my father became purposefully less careful knowing that the consequences, though painful and potentially dangerous, could also be remunerative and leisurely. When I heard that mum had been fired but was suing the company, I took from her delighted tone over the phone that this was something like another scam. She had been in the supermarket – now back on the floor and working as she had started offering people crackers with a bit of a new meat spread thumb-printed onto the dusty tile of a cream cracker when she took ill and was violently sick all over the tray and with another back splash to hit a couple of the waiting customers. In a rash display of corporate anger, mum’s boss assumed she was drunk and fired her on the spot. Unfortunately, this meant that they had no actual evidence that she was drunk. And when she went to the doctor because the nausea wasn’t going away, the tests came back positive for pancreatic cancer. ‘And so, the shoe is on the other foot now,’ she gleefully reported.

The legal case would go well for mum and the company would settle out of court for an undisclosed sum. Undisclosed I hasten to add even to me. My mum and dad wanted to hint that the settlement was astronomical and I’m sure it was generous, but they never wanted to give me any specifics. They didn’t really trust me. It was strange knowing that I was now older than both of them when they had had me as a baby. I could look at the photographs, faded and yellowy, collected in greasy packets under the bed and see how young they were. As I’ve said. I could easily have beaten my dad up then. Easily have killed both of them for that matter though I obviously would have no reason to. The problem with going home – the uneasiness I felt that prompted my long drives across the country – was the nostalgia that hit me like a wave of paralysing heartache. You almost wanted to succumb, but you knew if you did, something would tear inside you. Every time I came home, I would walk to Hampton Rock or up to the fell and stand there almost as if I was waiting for my younger self to appear on the path below me or walk across the sands. What kind of conversation would we have? Would my future progress reassure and hearten my young self, or would it appal?

Children are innocent. I remember a time when all I wanted to be was good. Mum had her Catholicism which she had brought with her from Ireland like an ugly heirloom she meant to throw away but stubbornly kept because the people around her didn’t seem to like it and she wanted to irk them. I missed the full blow of her revived religiosity. Taylor told me about it later. The praying, the kneeling, the stories of Jesus and the Saints, the Martyred Saints. I got to be an altar boy for about a year, but mum couldn’t be arsed with the going to mass as the priest insisted on three services a week. And though the Tuesday and Thursday masses were relatively short affairs, there was the price of petrol to think of. It was a pity because I enjoyed being an altar boy, being part of the ceremony. I enjoyed praying and I loved confession. The idea that you could go and tell someone everything you’ve done in a darkened box, the light finely shredded by the grate, and you would be forgiven with crisscrossed shadows falling on your innocent face was a delicious idea. I understood that mass was a drone of boredom but to be a participant meant you were usually alert to what you were doing and the various movements, gestures, responses and tasks you had to carry out. For me, the most attractive part of mass were the candles. We would light them at the start, we carried one each, tilting them slightly so the hot wax would run down the side over the cup of the candle holder and scald our hands and fingers; we placed them on the altar and at the end, when all was over, we would snuff them out with spit wettened fingers and peel the cooled wax from our fingers and hands. To this day I can sit and look at a candle burn until it burns all the way out and the wick is snuffed by its own melted wax. Fire was a doorway to somewhere else. Another universe of interest.

It was this kind of memory that would assault me when I was home. Lying in my bedroom, huge in my old bed, and staring at the ceiling self-harmed by the shadow the light outside the window cast of the thorny tree in the front garden.

The cancer dealt with mum’s weight problem in short order. In an irony that was lost on no one, least of all herself, she looked better and better, younger and younger, the closer she got to death. From the porridgey pudge, her face came through definite and vertical, and her eyes brightened. She stopped drinking. She totally lost any taste for it and even the smell of it from dad was too much for her to bear. She would push him away when he wanted to hold her and kiss her.

‘You smell like a brewery tart, Larry,’ Mary said.

Likewise, cigarettes were put out for the last time. Her addictions dropped from her like sated leeches. And she withered. She soon passed her ideal bodyweight/height ratio and passed into the land of the skeletal, the concentration camp survivor. Her life had become hospital corridors and appointments; bags from the chemist shop that looked like a weekly shop; pills prepared every Sunday for the week in a plastic container with differently coloured am and pm compartments for each day. The doctor had privately told her a year – she told Taylor on one of her rare return visits, but not me or dad – and she died exactly to the day a year later.

I got compassionate leave to attend her funeral. Dad sat between me and Taylor and wept in a way that was pitiful. He would keep straightening up and gasping for air and he would nod and smile and try to say something and look at the ceiling and say, ‘Oh God’ and then he would bow again and his face would tremble and collapse and his body would be wracked by sobs as if he were vomiting. He clenched my hand on one side and Taylor’s on the other. At the reception that was held at the golf clubhouse, he drank himself into a stupor and I had to carry him to the car – a green Audi – and drive him home and put him to bed in a house that now felt empty even when we were in it.

Taylor made a cup of tea for both of us and also opened a bottle of Bulgarian red wine she had brought home from the golf clubhouse. I let her pour me a glass, but I didn’t touch it. She ignored the tea and drank the wine.

‘Strange being back here,’ she said.

I nodded.

‘Do you get back much?’

‘No,’ I said.

She told me about mum phoning her about the cancer and telling her about the diagnosis.

‘I meant to come back, Sam,’ she said. ‘I had this idea that I would just drop everything and come back and I don’t know … nurse her or something. Spoon-feed her chicken soup and bring clean towels to her bedside table. Give her baths and all that. But I never did. I could have. My boss told me to take as much time as I needed, but I don’t know… I made excuses and didn’t do it. I don’t think mum would have really wanted me here. She would have got angry at me in no time. It would have been dreadful. And anyway, we don’t just drop stuff, do we? We think we will. We think these moments will be devastating but they aren’t, are they Sam? At least not the way dad is.’

We put the lights on because it was getting dark and Taylor lit the coal fire; something she had obviously not forgotten how to do.

‘There’s no right way of feeling,’ I said, quoting Uncle Mike. He’d said this when he had got me in a bear hug and squeezed me.

‘Look at you, look at you,’ he said, holding me at arm’s length the better to do it. I couldn’t cry or show any emotion the way other people did. I thought of putting my face in my hands now and then, or blowing my nose, but through the years I’ve noticed that people are far more disconcerted by fake displays of emotion than they are by no emotion. If you show no emotion, they think that it’s deeper than the visible eye can penetrate, whereas if they catch you wiping away a tear that is obviously not there than they really start to wonder. I told Mike that I felt empty and hollow and he told me that there was no right way to feel. I told him that I supposed it hadn’t hit me yet.

Not really.

‘It all seemed so…’ and then I shrugged and had nothing more to say and he nodded as if he understood exactly what I had said. Taylor didn’t nod. She looked at me.

‘You don’t feel anything?’ she said.

I frowned and nodded. ‘Perhaps it hasn’t sunk in.’

She shook her head. ‘No, I mean, you don’t feel anything. Ever. That’s still the case, isn’t it? With you?’

My frown must have turned deeper because she laughed. She loved tormenting me when I was a kid and she could make me so furious. She could press all my buttons; my newly dead mum would say. She now had long straight auburn hair and wore a cardigan with a broach that should have been worn by an old lady but somehow suited her. I knew that she would continue to torment me, so I did what I used to do when she chased me around the garden, I fell down. I gave up.

I surrendered.

‘I know that I don’t feel anything, Taylor. I know what I am.’

She nodded and widened her eyes as if to say to someone else in the room: ‘see what I have to deal with?’ But there was no one there but us. She sat for a moment thinking, sipping at her wine and then pouring herself a fresh glass. Filling it to the brim, careless of restraint.

‘Have you… hurt people, Sam?’

I laughed. ‘I’m in the army. Of course, I’ve hurt people.’

‘Of course, you are. You know what I mean.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I thought about you a lot these years. While I’ve been away.’

I stared at her for a long moment. Having a think. How serious was she? How much had she already worked out? She had had time.

‘I’ve gone through the checklist. And I’m pretty much ticking every box. But there’s no necessary correlation between that and murder. I come out as a sociopath. The test I mean. That’s how it describes me. I understand that. I mean I’ve read about it and it seems like an accurate description to me. And I sometimes wish I could be like other people. I see everyone and I want to join in. I want to feel what they feel, but most of the time it feels good. It feels better to be like me than to be like them. Look at dad today. Why would I want to feel that? Why would I want to be reduced to such a state?’

‘It’s not a reduction,’ she said, and I was surprised by an edge of anger in her voice.

‘I thought we were just talking here.’

She looked at me.

She didn’t just look at me: she saw me.

‘I didn’t come to see mum and dad because of you,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t bear the thought that we’d meet and here we are again. Happy as can be.’ She sang the end. ‘All good friends and in wonderful company.’

‘That’s …’

‘Don’t bother,’ she said. ‘I always knew there was something off with you. I mean you were always weird. Always strange. But kids are weird themselves. They’re pretty much psychos and you’re waiting for them to develop inner lives, emotions, that sort of thing. And we didn’t have exactly the most normal or stable of households. The drinking, the physical and emotional abuse…’

‘The what?’

‘It was understandable you’d withdraw somewhat,’ she said.

‘You talk like you were twenty years older, or something,’ I said. ‘You talk like television.’

‘The little things you stole and destroyed. That was fine. The fires you loved, okay. I suppose. A phase. The lies were annoying but nothing that unusual. But killing Allan… killing your own dog. Tying him to the train tracks. And that dog didn’t even move. Just lay there thinking it was some game. That was … sick.’

‘What are you talking about? I didn’t kill Allan. That was Stephen Pritt.’

‘Really? You told me it was Elliot Comb.’

‘It was one of those guys. They did it. I can’t remember which. Perhaps it was both. I was really upset.’

‘No, you weren’t. You didn’t cry at all. And it was you. That’s why they stopped being friends with you.’

I laughed.

‘People get so upset by animals. People hurting animals. Don’t hurt animals, they say as they chomp down on their sausage rolls and hamburgers.’

‘Is that what you tell yourself?’ she said. ‘That everyone else is a hypocrite and you’re the only one to see the world clearly as it is?’

‘I…’

‘Because if that’s so, how come you need to lie so much?’

I took a deep breath. This was not as pleasant a conversation as I had hoped. It was my fault. I had a list of questions memorized to ask Taylor about her life in London, her job, her career, her hope for the future – was the music a real thing she was doing now, or would she get a proper job? Did she see herself having kids? For instance – was there anyone in her life now? But I had let her take over the conversation and she had launched it in an aggressive way straight towards me and my failings. I should say something, change the subject, laugh it off. But she wouldn’t let me speak.

‘Tell me one thing.’

‘What?’

‘Did you actually join the army?’

‘This is silly,’ I said. ‘I don’t know what’s gotten into you. I’m … not going to sit here …’

This was one solution. I could stand up and walk out, right now. Righteous anger. Fury even. She wouldn’t be convinced. I had admitted to not feeling such things and now I was going to complain of hurt feelings. And I tended to overdo rage when I did try it. She was watching me now and I realized that she was scared. She had gone too far. Further than she intended. She probably had another conversation prepared. Similar to the one I had memorized. She wanted this conversation to stop as much as I did. She was upset by mum and that and the Bulgarian red had led her down this wine dark path, but now she was here, she was thinking: I’m alone in the cottage with Sam: dad’s snoring in a stupor upstairs.

‘You are scared of me,’ I told her.

‘I’m scared you have hurt people, or you are going to hurt people. You’re like a staircase without a bannister. Do you understand what I’m saying? Is there anything I could do or say that would make you try and get some help?’

‘Help? Ha!’

I laughed and laughed and laughed.

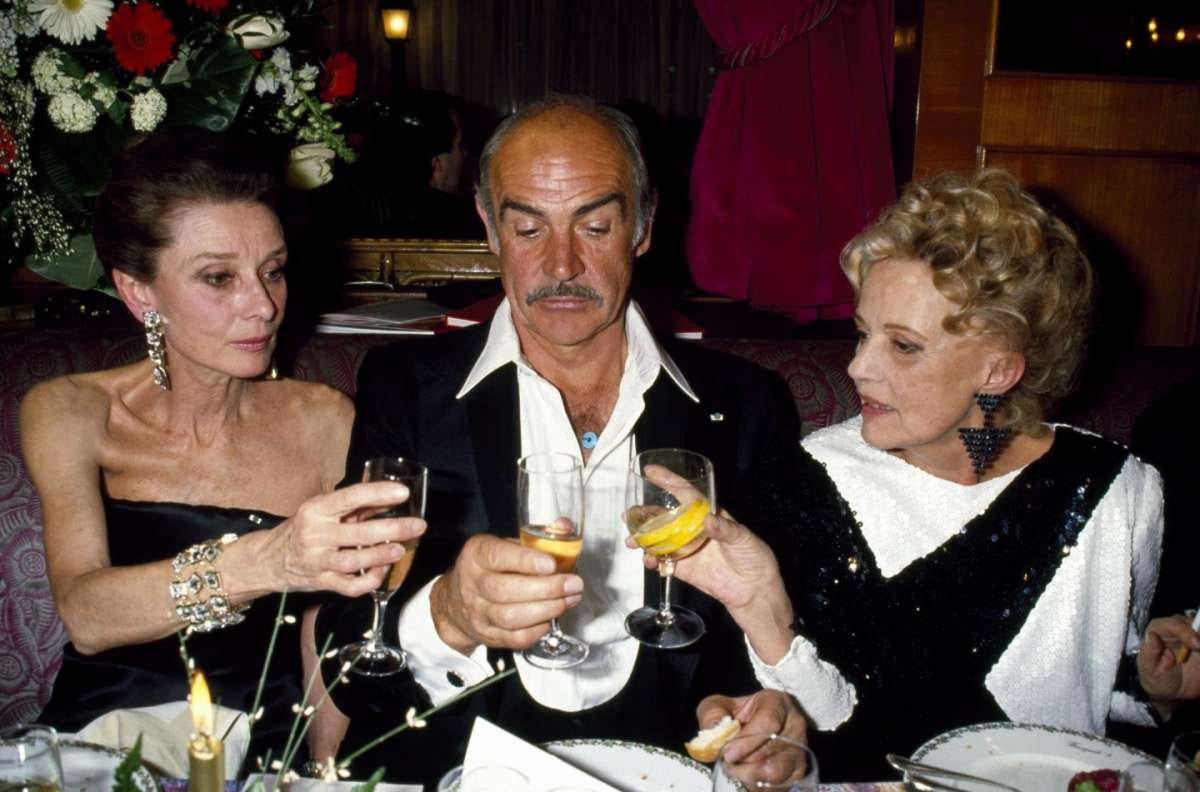

I laughed – a full throated laugh of derisive good humour – laughed so hard that tears leapt to my eyes and I enjoyed the feeling they made when they ran down my face. It was a funny ticklish sensation. I put my hand in my mouth and bit the skin between my thumb and forefinger. That night, I woke up from a cobwebbed dream of ghosts following me and in the middle of the night I went downstairs and put my wellingtons on and closed the door quietly behind me, crossed the railway line and the golf course and out onto the sand, wondering if this too was a dream, but you never feel cold in a dream. Not real cold. The tide was way out on the horizon and the wind was shivering cold and the shivering stars were out. Orion the Hunter, Cassiopeia, the wonky W. I saw the black eye socket of the rock where I had met Sean Connery, but I walked squelching across the black sands towards the distant rumour of the sea, trying to avoid the sinking sand and the pools, shoved occasionally by a sudden thrust of obnoxious wind.

It felt glorious to be out there, under an enormous night sky, bigger than God. The whole galaxy looking down. A witness to my existence. My continued survival. My continued role as the centre of the universe around which all existence extended and depended. Where would you be stars, without me? Thank me, world, for your continued orbit. Praise me, God, because without me you wouldn’t have a job. You’d have to stay in playing Sega.

The sound of the terns keened a sad minor note and the waves plipped and plopped somewhere in the near darkness. I walked along the bank of a channel dug into the crumbling sand by the River Duddon, on its way to the sea. There was a chance the tide was coming in and it could come in with fatal speed. A sudden rush. I hurried as I walked because I needed to meet it. I skirted the bank and I wondered what would happen if I did get caught out here. I didn’t think it would be a problem. I had survived worse swims. This is what the soft and squishy didn’t understand, the people like Taylor. They were people who couldn’t survive without telephones and supermarkets and acoustic guitars, television and telephones and computers. Telephones, telephones, telephones and soon email. You could drop me anywhere in the world and I had been trained by the best to survive regardless of the hostility of the environment or even the local population. Had I ever hurt anyone? The amount of brotherly love it took on my part not to kill Taylor that night was testament to the depth of my feelings – yes, feelings – for this confused young woman with the songs she was writing and the hopeless series of jobs in advertising agencies. She would live and become famous and everyone would love her. She would be a regular guest on Jools Holland and other more successful music programmes; she would grace the covers of Culture Segments of all the major newspapers at one point or another. As well as splashes on fashion magazines and her home would be drooled over on multiple levels. She would have one extremely successful international hit that allowed her to break into the United States and she would go there and live and perform there, eventually applying for and receiving citizenship. She would not ever acknowledge my role in her success even as it stalled at the level that she achieved when she was 32 and never went further. She was already something of a nostalgia act in her 40s, though for a devoted fanbase the music she continued to produce and write would continue to directly speak to their own personal experiences. It would be popular at weddings and funerals. Her live shows – according to the reviews which I read over the years – achieved a level of intimacy that no other performer came close to. The voice was failing they would say, and she allowed session musicians now to perform the solos she had recorded herself and had contributed to her reputation as an artist, a beautiful player of the guitar, and not just a pretty face and a gorgeous melted caramel voice. She would never say, on accepting the Grammy she won: ‘I’d like to thank my brother, if it wasn’t for him generously not killing me the night of my mother’s funeral, I wouldn’t have recorded this song and I wouldn’t be here today to receive this award.’ Interviews referred to a dark childhood, abuse she came clean about in strategically timed confessions. A fresh revelation came out just in time for a new release, or a book of poetry inspired by her lyrics. The confession of alcoholism and other addiction issues later on would likewise be timed for maximum effect. Exclusives. If it gets the cover. And then there was rehab and recovery and that became the subject matter of another album and a ‘searingly honest’ autobiography, which was so poorly written I knew for sure she had written it without the aid of a ghost writer.

The acting career – it had to be said – did not go as well as her music. She played some roles in cult movies, small independent things, and those were her most successful. Anything more substantial and she didn’t have the requisite presence to fill the screen or hold the eye. She didn’t move the air. The filmmakers would endeavour to add a song for her to perform so that she could feel comfortable and they could sell that as part of the package. She came alive when she sang, and this was evident to all. When she returned to England, it was always to promote something, and she would play up her ecky-thump northern accent and her humble origins on Graham Norton. It seemed strange that this woman who was on good terms with many of the superstars was really, at heart just like us. We felt vicariously satisfied with our position in the world, because we too were in effect rubbing shoulders with Brad Pitt and all the other stars. And it helped that despite all the adulation and obvious wealth, she was so obviously so nakedly not happy.

Aside from the addiction and her fluctuating weight, she also had a knack for choosing the most inappropriate men to get into relationships with, men who possessed a cruel sense of humour and an irresistible amount of power that had nothing to do with what she did. Electronic tsars and hedge fund managers. They patronised her and were unimpressed by her fame and achievements, ultimately dispensing of her when she became too much trouble. They – like the addiction problems and the abusive childhood – also became subject matter for new albums, new material. There were some men who were specifically linked to albums and again if you asked that fanbase they knew each one, like a military historian studying the battles of Julius Caesar or Napoleon Bonaparte. I met her several times again over the years. And we were good at putting on a show before others. She was careful never to be left alone with me, assistants hovered like dragonflies, and I think she had decided to bury her knowledge, bury it as deep as it would go. She had the bad luck of dying on the same day as David Bowie.

Do you remember?

Few do.

She had woken up when I came back in. My feet and the bottom of my trousers were soaking wet and my face and ears were numb with the pinching cold. I was in her room holding the pillow in my hands. I must have been a shape in the darkness. Nothing more. She said my name sleepily and then once more, alert. There was a sliver of a plea in there. Not enough to excite an emotional response, not enough to make the moment totally real. It could be a dream, she was saying, I felt. I felt she wanted to have deniable plausibility of her own potential death.

Would she say tomorrow morning – if she saw tomorrow morning – would she say ‘I had the strangest dream last night. I dreamt you were in my room holding a pillow with a murderous glint in your eye’? I put the pillow down and I stroked her face once with my hand.

It wasn’t a caress so much as a very soft slap. A promissory note of an assault. An indication that no, this wasn’t a dream. I am here. And I can do anything. I could have killed you before you woke up. Without knowing it, you could have already said goodbye to your life, the moment you drifted to sleep. Your last experience would have been a dream. But isn’t that always the case anyway.

Just ask the ghosts. I’ve got a few now following me and doing my bidding.

And when we met a decade later and then again, a decade or so after that we both knew that everything she had, everything she had achieved was because of a decision I made that night. A forbearance on my part.

Her success and career were made possible because I didn’t suffocate her that night. Not killing someone was almost like giving birth to the rest of their lives. It gave me a great sense of power, ownership even. Everything you do from this point forth, belongs rightfully to me. Everything. I would never tell her this. But we both knew.

I rested in the knowledge.