On New Year’s Day, the United Kingdom along with the Republic of Ireland and Denmark, entered the European Economic Community. Richard Nixon was sworn in for a second term as President of the United States of America and the American involvement in the Vietnam War formally ceased with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords. As with many such moments, it came down to furniture. The North Vietnamese wanted a round table so that everyone was seated an equal distance one from the other whereas the representatives of the South wanted a rectangular table so the two sides of the conflict could be clearly represented.

Roger Moore was busily shooting Live and Let Die, his first outing as James Bond. He’d got the role after Sean Connery had turned down the record breaking fee of five and a half million dollars. The studio wanted an American to take over the role and had touted Burt Reynolds and Paul Newman to play the role, but Moore had managed to get the part. He’d wanted the part, having become famous for TV roles such as The Saint. Unfortunately, both Moore and his leading lady Jane Seymour had contracted dysentery while shooting in Jamaica. He’d also had to go to the hospital because of his kidneys, but he was happy with the work they were doing and was confident that this was the moment where he would be taken to another level of fame. He was also determined not to make a hash of it the way that man Lazenby had. He also liked that there were little touches to his Bond that meant he wouldn’t be compared to Connery. He smoked cigars and drank whiskey, replacing the cigarettes and vodka martinis.

My dad had seen two dilapidated houses on the hill overlooking Askam-in-Furness. They were over a hundred years old, derelict and overgrown with nettles and brambles. The roof had collapsed. They were built of slate from the small quarry at the rim of the fell that loomed above. They were on the end of a row detached cottages, a small hamlet called Paradise. Peter had asked how much it would cost to buy them. A friend of his, Keith Dixon, had put him on to them. They were owned by a woman called Miss Peroux, a physiotherapist who lived in the south. Peter went down to see her and Miss Perroux like him and agreed to sell the house and the land for £2600.

Rosaleen couldn’t really see what they could do with the houses, but Peter was full of enthusiasm and complete confidence. He’d rebuild the houses as one house. The view was amazing, especially when the sun set over the Irish Sea and Black Combe became a darkened slope. You could see all the way up the estuary over Scafell to Coniston Old Man to the north and down to Walney Island in the south. Peter’s parents had moved to Auntie Marjorie’s a few years ago. They’d given Peter the house on Marsh Street and he’d given them £600 to pay for the extension where they lived at Auntie Marjorie and Uncle Derek’s. Grandad Joseph had died a year earlier and now Grandma Prudence was sick as well. Auntie Marjorie found it difficult.

Peter sold the house on Marsh Street for £3500 to a district nurse from Altrincham. and applied for a £2500 mortgage. With the money the houses at 17 Paradise were bought along with the land as well as a small caravan purchased from Irish travellers. It came with solid furniture. Oak.

Judith Trim listened expectantly as her husband set the tape machine up. She’d heard pieces already and whole songs in various version, but this would be the first time she would hear the whole album all the way through. Her husband wanted her to hear it without interruption and so she was careful to keep her comments to a minimum, but at the end of the last song, she couldn’t help it. She burst into tears. Roger Waters was abashed by the reaction and surprised. He knew it was good, but listening to it with Judith and trying to gauge her reaction she realized the album was something special. It had been a lot of fun to record. The band were all on the same page, which hadn’t always been the case. The fact was they had plateaued over the last few years and there was always the chance that they’d missed their moment, with no real hits since Syd had left. But Dark Side of the Moon had hit a nerve and now he heard that it did hang together. It made more sense.

Martin Cooper was in New York the first week of April, walking between 53rd and 54th Street. He took the phone out of the briefcase and dialled the number he’d memorized. He heard the ringtone and then heard Joel Engel pick up on the other end and say hello. “Hiya Joel,'“ Martin said. “This is Martin Cooper from Motorola.”

Joel sounded surprised. They were rivals. Friendly, but still working for the opposition: Bell Laboratories at AT&T.

“Guess where I’m calling you from.”

Joel would say he couldn’t remember the phone call and what he said, if he said anything. There was a chance he swore. He’d always wanted to be on the first mobile phone call, but he wanted to be the one making it, not receiving it.

That week I almost died.

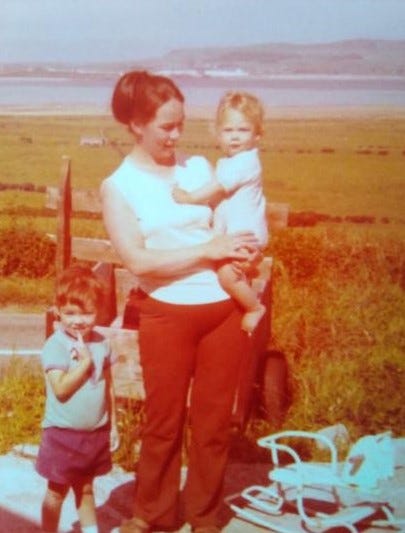

I was in the caravan, in my crib. Peter was at work at Glaxo, a chemical plant in Ulverston. Francis was eating a boiled egg at the table that came out from where the bed folded up during the day. Rosaleen was spooning medicine into my mouth. I’d had a fever and she was hoping it would help. But instead I gave a sudden scream and began to convulse. My arms stretched out and grabbed the sides of my crib and my back began to arch as my muscles spasmed. Rosaleen didn’t have a telephone, or anyone close by. She ran to the next door neighbour’s house. Dot Gedling was there and she let Rosaleen called Dr McGranthin. He was in Askam and within five minutes he’d driven up to the house. At this point, I had turned blue and my skin was so hot it burned to touch.

Dr McGranthin took out a little oxygen tank the size of a candle from his bag and with a little facemask fitted around my head, couldn’t help but brag about his new gadget as he pumped oxygen into my lungs and they waited for the ambulance to arrive. “I only got this last week,” he told Rosaleen. “A fascinating little contraption.”

Francis watched. Dot Gedling took his hand and led him to her house until Peter arrived from work, where Rosaleen had telephoned him to tell him to come home immediately.

I spent a week in the Devonshire Road Children’s Hospital, right next to the cemetery. They opened the window to the winds and directed fans at my cot where I lay in order to cool me down. Dr McGranthin cheerfully concluded that I’d have died if not for that little gadget which had just arrived the week before. I’d inhaled the medicine instead of swallowing and had been choking, my throat swollen from the illness already.

Every morning Terrence Malick drove to the studio met with his editor, Billy Weber. They sat and watched the Watergate hearings which were being shown live across all three networks. When they finished, they went back to editing his film Badlands. It was a slow process. Nixon had considered resigning before the hearings began. He’d talked to his family about the possibility. Spiro Agnew - his vice - would’ve become President. A few months later Agnew himself would resign over a financial scandal.

The caravan was cosy with the heater, but the toilet was behind the house and in the dark Rosaleen hated it. It had a slanted roof and a rickety door which didn’t reach to the floor. There were animals in the hedgerows and sheep in the top field. Peter spent every night working in the house until midnight. Then he woke up at six and went to work for the day. He worked weekends. The planning permission had been prepared by his sister Vera’s husband, Brian. Brian was now a building inspector down south in Bedfordshire, but he did the drawings for dad and in the summer they came up to stay. Peter hired a caravan for Vera and Brian. His eldest brother, his only brother, Jack took a week off work, as had Brian. That week the lumber merchants Johnson’s delivered the roof joists. Jack and Brian had booth been joiners - Jack still was in fact. Peter was an electrician but he had wanted to be a carpenter. His dad thought that one carpenter in the family was enough. Whenever Peter needed help someone would come round. People in Askam and Ireleth liked the adventure of watching the house taking shape on the fell. Johnny Clapham, a portly man who once worked the railways and always wore navy blue denim dungarees, walked the road and stopped to talk with Peter, even though Peter would rather get on with the work while he could. Johnny Clapham had been born in the house. One of ten children. He was in his seventies. And the house was old then.

The Seers Tower in Chicago had its roof put on and became the tallest building in the world. It was 1,451 ft tall. Vesna Vulović had fallen the equivalent of 23 Seers Towers to the ground and survived. She still walked with a limp and would do for the rest of her life. She visited the village where she had landed and met the granddaughter of the man who had saved her life and who had been named after her. Her celebrity was beginning to fade. Her parents never recovered from the shock of what had happened.

In November, Pioneer 10 arrived at Jupiter and sent back photographs. It was the closest images anyone had ever seen of the gas giant, the biggest planet in the Solar System. The approach took it past many of Jupiter’s moons. It approached Jupiter at a speed of 37,000 miles per second, using the planet’s gravity to produce a slingshot effect that had never been tried before. It worked perfectly and sent Pioneer 10 heading into the outer reaches of the Solar System at an escape velocity which would see it enter interstellar space.

Christmas Day was spent with Rosaleen’s father and sister Maureen on Barrow Island. Frank Fagan had come from Ireland to work in Barrow-in-Furness during the Second World War. He’d spent the first part of the war as a fireman in London during the Blitz of 1940 and hadn’t enjoyed it one bit. Returning to Belfast he’d ask the Labour Exchange to send him somewhere else. They’d given him the choice of Liverpool or Barrow-in-Furness. Reasoning that if he’d never heard of the place, chances are Adolf Hitler hadn’t either, he opted for Barrow-in-Furness, the small industrial town just south of the Lake District. He arrived in May of 1940 just in time for the first bombing raid which was going to be known as the Barrow Blitz. 83 people died and 310 were injured. There were few shelters and people hid in hedgerows. Frank smoked small cigars, drank Guinness and whisky and liked a little bet. Everything in moderation. He was a quiet man but could have a foul temper at times. Moody.

Maureen was the first to feel ill. Then Rosaleen began to feel ill too. Peter and Rosaleen drove home with Francis and I and by the time we were in the caravan everyone was ill. It was a hard few days in the caravan and not much of a Christmas. The presents weren’t even opened until a few days later.